(Richard King) Laoch

Image by Fergal of Claddagh

Click here for the first part of the story of DEIRDRE OF THE SORROWS www.flickr.com/photos/feargal/5122512441/in/photostream/

BUT all this while the cunning, cruel heart of Conor was planning his revenge. For though he was an old man with grown-up sons of middle age, he had begun to feel affection for the child who had been sheltered by his care, and who looked to him as her protector and her friend. And after all the years that he had waited for the girl, to have her plucked away beneath his eyes just when she was of age to be his wife, aroused his bitter wrath and jealousy. Deep in his heart he plotted dark revenge, but it was hard to carry out his plan, for well he knew that of his chiefs not one would lift his hand against the sons of Usna. Of all the Red Branch Champions those three were loved the best; and difficult it was to know which of the three was bravest, or most noble to see. When in the autumn games they raced or leaped or drove the chariots round the racing-course, some said that Arden had the more majestic step and stately air; others, that Ainle was more graceful and more lithe in swing, but most agreed that Naoise was the most princely of the three, so dignified his gait, so swift his step in running, and so strong and firm his hand. But when they wrestled, ran or fought in combats side by side, men praised them all, and called them the "Three Lights of Valour of the Gael."

When his plans were ripe, Conor made a festival in Armagh, and all his chiefs were gathered to the feast. The aged Fergus sat at his right hand and Caffa next to him; close by sat Conall Cernach, a mighty warrior, still in his full prime, and by his side, as in old times, Cú Chulain sat. He seemed still young, but of an awesome aspect, as one who had a tragedy before him, and great deeds behind; and, for all that he was the pride of Ulster's hosts, men stood in dread before him, as though he were a god. Around the board sat many a mighty man and good prime warrior seasoned by long wars. But in the hall three seats were empty, and it was known to be Conor's command that in his presence none should dare to speak the names of Usna's banished sons.

This night Conor was merry and in pleasant humour, as it seemed. He plied his guests with mead and ale out of his golden horns, and led the tale and passed the jest, and laughed, and all his chiefs laughed with him, till the hall was filled with cheerful sounds of song and merriment. And when the cheer was bravest and the feast was at its height, he rose and said: ' Right welcome all assembled here this night, High Chiefs of Ulster, Champions of the Branch. Of all royal households in the world, tell me, O you who travel much and see strange distant lands and courts of kings, have ye in Scotland or in Ireland's realms, or in the countries of the great wide world, ever seen a court more princely than our own, or an assembly comely as the Red Branch Knights? “

“We know not," they all cried, "of any such. Your court, O Conor, is of all courts on earth the bravest and the best."

"If this be so," said wily Conor, “I suppose no sense of want lies on you; no lack of anything is in your minds? “

“We know not any want at all," they said aloud; but in their minds they thought, “save the Three Lights of Valour of the Gael."

“But I, O warriors, know one want that lies on us," Conor replied, “the want of the three sons of Usna fills my mind. Naoise and Ainle and Arden, good warriors were they all; but Naoise is a match for any mighty monarch in the world. By his own strength alone he carved for him and his own a princely realm in Scotland, and there he rules. Alas! That for the sake of any woman in the world, we lose his presence here."

“Had we but dared to utter that, O Great Warrior, long since we should have called them home again. These three alone would safely guard the province against any host. Three sons of a border-lord and used to fight are they; three heroes of warfare, three lions of fearless might."

“I knew not," said Conor craftily, "you wished them back. I thought you all were jealous of their might, or long ere this we should have sent for them. Let messengers now go, and heralds of Conor to bring them home, for welcome to us all will be the sight of The sons of Usna."

“Who is the herald who shall bear that peaceful message?” they all cried. “I have been told," said Conor, “that out of Ulster's chiefs there were but three whose word of honour and protection they would trust, and at whose invitation Naoise would come again in peace. With Conall Cernach he will come, or with Cú Chulain, or with great Fergus of the mighty arms. These are the friends in whom he will confide; under the safe-guard of each one of these he knows all will be well."

“Bid Fergus go, or Conall or Cú Chulain," the warriors cried; "let not a single night pass by until the message goes to bring the sons of Usna to our board again. Most sorely do we need them; deeply do we mourn their loss. Bring back the Lights of Valour of the Gael."

" Now will I test," thought Conor to himself, “which of these three prime warriors loves me best." So supper being ended, Conor took Conall to his ante-room apart and set himself to question cunningly: “Suppose, loyal soldier of the world, you were to go and fetch the sons of Usna back from Scotland to their own land under your safeguard and your word of honour that they should not be harmed; but if, in spite of this, some ill should fall on them not by my hand, of course and they were slain, what then would happen, what would you do?"

“I swear, Great Conor," said Conall, "by my hand, that if the sons of Usna were brought here under my protection to their death, not he alone whose hand was stained by that foul deed, but every man of Ulster who had wrought them harm should feel my righteous vengeance and my wrath."

'I thought as much," said Conor, “not great the love and service you dost give your lord. Dearer to you than are The sons of Usna."

Then sent he for Cú Chulain and to him he made the same demand. But bolder yet Cú Chulain made reply: “I pledge my word, Great Conor, if evil were to fall upon the sons of Usna, brought back to Ireland and their homes in confidence in my protection and my plighted word, not all the riches of the eastern world would bribe or hinder me from severing your own head from you in lieu of the dear heads of The sons of Usna, most foully slain when tempted home by their sure trust in me."

“I see it now, Cú Chulain," said Conor, “you profess a love for me you do not truly feel."

Then Fergus came, and to him also he proposed the same request. Now Fergus was perplexed what answer he should give. Sore did it trouble him to think that evil might befall brave The sons of Usna when under his protection. Yet it was but a little while since he and Conor had made friends, and he come back to Ulster, and set high in place and power by Conor, and well he knew that Conor doubted him; and such a deed as this, to bring the sons of Usna home again, would prove fidelity and win Conor's affection. Moreover, Conor spoke so guardedly that Fergus was not sure whether Conor had ill intent or no towards the sons of Usna. For all he said was: "Supposing any harm or ill befall the sons of Usna by the hand of any here, what wouldst you do? “

So after long debate within himself, Fergus replied: "If any Ulsterman should harm the noble youths, undoubtedly I should avenge the deed; but you, Great Conor, and your own flesh and blood, I would not harm; for well I know, that if they came under protection of your sovereign word, they would be safe with you. Therefore, against you and your house, I would not raise my hand, whatever the conditions, but faithfully and with my life will serve you."

"It is well," the wily Conor replied, “I see, O loyal warrior, that you love me well, and I will prove your faithfulness and truth. The sons of Usna without doubt will come with you. Tomorrow set you forward; bear Conor's message to brave The sons of Usna, say that he eagerly awaits their coming, that Ulster longs to welcome them. Urge them to hasten; bid them not to linger on the way, but with the utmost speed to press straight forward here to Armagh."

Then Fergus went out from Conor and told the nobles he had pledged his word to Conor to bring back the sons of Usna to their native land. And on the morrow's morn Fergus set forth in his own boat, and with him his two sons, Ulan the Fair and Buinne the Ruthless Red, and together they sailed to Loch Etive in Scotland.

But hardly had they started than Conor set to work with cunning craft to lure the sons of Usna to their doom. He sent for Borrach, son of Annte, who had built a mighty fortress by the sea, and said to him, “Did I not hear, O Borrach, that you had prepared a feast for me? ' c It is even so, Great Conor, and I await your coming to partake of the banquet I have prepared." And Conor said, '; I may not come at this time to your feast; the duties of Land keep me here at Armagh. But I would not decline your hospitality. Fergus, the son of Roy, stands close to me in place and power; a feast bestowed on him I hold as though it were bestowed on me. In less than a week's time comes Fergus back from Scotland, bringing the sons of Usna to their home. Bid Fergus to your feast, and I will hold the honour paid to him as paid to me."

For wily Conor knew that if his royal command was laid on Fergus to accept the banquet in his stead, Fergus dare not refuse; and by this means he sought to separate the sons of Usna from their friend, and get them fast into his own power at Armagh, while Fergus waited yet at Borrach's house, partaking of his hospitality.

"Thus,” thought Conor, "I have the sons of Usna in my grasp, and dire the vengeance I will wreak on them, the men who stole my wife."

AT the head of fair Loch Etive the sons of Usna had built for themselves three spacious hunting seats among the pine-trees at the foot of the cliffs that ran landward to deep Glen Etive. The wild deer could be shot from the window, and the salmon taken out of the stream from the door of their dwelling. There they passed the spring and summer months, The sons of Usna of the white steeds and the brown deer hounds, whose breasts were broader than the wooden leaves of the door. Above the hunting-lodge, on the grassy slope that is at the foot of the cascade, they built a sunny summer home for Deirdre, and they called it the Grianán, or sunny bower of Deirdre. It was thatched on the outside with the long-stalked fern of the dells and the red clay of the pools, and lined within with the pine of the mountains and the downy feathers of the wild birds; and round it was the apple-garden of Clan Usna, with the apple-tree of Deirdre in its midst and the apple-trees of Naoise and Ainle and Arden encircling it.

And Deirdre loved her life, for she was free as the brown partridge flying over the mountains or as the vessels with ruddy sails swinging upon the loch. But in the winter they moved down to the broad sheltered pasture-lands that lay on the western side of the loch near the island that was in olden days called Oileán Chlann Uisne or the Island of the Children of Usna, but is called Oileán nan Ron or the Isle of the Seals to-day; and there they built a mighty fortress for Deirdre and the sons of Usna which men still call the Caisteal Nighean Righ Eirinn or the Castle of the Daughter of Conor of Ireland, and thence they made wars and conquered a great part of Western Scotland and became powerful princes.

One sultry evening in the late autumn, Deirdre and Naoise were resting before the door of her sunny bower after a day spent by the brothers in the chase. Below, their followers were cutting up the deer, and as they brought in the bags of heavy game, and faggots for the hearth, the voice of Ainle singing an evening melody resounded through the wood. Like the sound of the wave the voice of Ainle, and the rich bass of Arden answered him, as together the two brothers came out from the shadow of the trees, gathering to the trysting-place of the evening meal.

Between Naoise and Deirdre a draught-board was set, but Deirdre was winning, for a mood of oppression lay upon Naoise and his thoughts were not in the game. For of late, at evening, his exile weighed upon him, and little good to him seemed his prosperity and his successes, since he did not see his own home in Ireland and his friends at the time of his rising in the morning or at the time of his lying down at night. For great as were his possessions in Scotland, stronger in him than the love of his kindred in Scotland was the love of his native land in Ireland. He thought it strange, moreover, that of those three who in the old time loved him most, Fergus and Conall Cernach and Cú Chulain, not one of them had all this time come to bring him to his own land again under his safeguard and protection.

So, as they played, Deirdre could see that the mind of Naoise was wandering from the game, and her heart smote her, as often it had smitten her before when she had seen him thus oppressed, that for her sake so much had gone from him of friends and home, and his allegiance to Conor, and honourable days among his clan. Wistfully she smiled across the board at Naoise, but mournful was the answering smile he sent her back.

“Play, play," she said, “I win the game from you."

“One game the more or less can matter little when all else is lost," he answered bitterly.

But hardly had the unkind words passed from him, the first unkindness Deirdre ever heard from Naoise's lips, when far below, across the silent waters of the lake, he caught a distant call, his own name uttered in a ringing voice that seemed familiar, a voice that brought old days to memory.

“I hear the voice of a man from Ireland call below," he cried, and started up.

Now Deirdre too had heard the cry and well she knew that it was Fergus' voice they heard, but deep foreboding passed across her mind that all their hours of happiness were past, and grief and rending of the heart in store. So quickly she replied: “How could that be? It is some man of Scotland coming from the chase, belated in returning. No voice was that from Ireland; it was a Scotchman's cry. Let us play on."

Three times the voice of Fergus came sounding up the glen, and at the last, Naoise sprang up. “You are mistaken, damsel; of a certainty I know this is the voice of Fergus."

“I knew it all the time, whose voice it was," said Deirdre, when she saw he would not be put off.

"Why then did you not tell us?" Naoise asked. '

“A vision that I saw last night hath hindered me," replied the girl. "I saw three birds come to us out of Armagh from Conor, carrying three sips of honey in their bills; the sips of honey they left here with us, but took three sips of our red blood away with them."

“What is your read of this vision, O Damsel? “Naoise asked.

"Thus do I understand it," Deirdre said; "Fergus hath come from our own native land with peace, and sweet as honey will his message be; but the three sips of blood that he will take away with him, those three are ye, for ye will go with him, and be betrayed to death."

"Speak not such words, O Deirdre," cried they all; “never would Fergus thus betray his friends. Alas! That words like this should pass your lips. We stay too long; Fergus awaits us at the port. Go, Ainle, and go, Arden, down to meet him, and to give him loving welcome here."

So Arden went, and Ainle, and three loving kisses fervently they gave to Fergus and his sons. Gladly they welcomed the wayfarers to Naoise's home, and led them up; and Naoise and Deirdre arose and stretched their hands in welcome; and they gave them blessing and three kisses lovingly, for old times' sake, and eagerly they asked for tidings of Ireland, and of Ulster especially.

“I have no other tidings half so good as these," said Fergus, “that Conor waits for you to give you welcome back to Armagh, and to the Red Branch House. I am your surety and your safeguard, and full well ye know that under Fergus' safeguard ye are sure of peace."

“Heed not that message, Naoise," Deirdre said; “greater and wider is your lordship here, than Conor's rule in Ireland."

“Better than any lordship is one's native land," said Naoise; “dearer to me than great possessions here, is one more sight of Ireland's well-loved soil."

“My word and pledge are firm on your behalf," said Fergus; "with me no harm or hurt can come to you."

"Verily and indeed, your word is firm, and we will go with you."

But to their going Deirdre consented not, and every way she sought to hinder them, and wept and prayed them not to go to death.

"Now all my joy is past," she said; "I saw last night the three black ravens bearing three sad leaves of the yew-tree of death; and O Beloved, those three withered leaves I saw were the three sons of Usna, blown off their stem by the rough wind of Conor's wrath and the damp dew of Fergus' treachery."

And they were sorry that she had said that.

"These are but foolish women's fears," said they; “the dropping of leaves in your dream, and the howling of dogs, the sight of birds with blood-drops in their bills, are but the restlessness of sleep, O Deirdre; and verily we put our trust in Fergus 5 word. Tonight we go with him to Ireland."

Gladsome and joyful were the three brothers then; they put all fears away from them, and set to prepare them for their journey back to Ireland's shores. And early the next morning, about the parting of night from day, at the delay of the morning dawn, they passed down to their galley that rocked upon the loch, and hoisted sail, and calmly and peacefully they sailed out into the ocean. But Deirdre sat in the stern of the boat, and her face was not set forward looking towards Ireland, but it was set backward looking on the coasts of Scotland. And she cried aloud, “O Land of the East, My love to you, with your wondrous beauty! Woe is me that I leave your lochs and your bays, your flowering delightful plains, and your bright green-smooth hills! Dear to me the fort that Naoise built, dear the sunny bower up the glen; very dear to my heart the wooded slope holding the sunbeams where I have sat with Naoise." And as they sailed out of Glen Etive she sang this song, sadly and sorrowfully:

"Farewell, dear Scotland of the free,

Beloved land beside the sea,

No power could drag me from my home,

Did I not come, Naoise, with you.

Farewell, dear bowers within the Glen,

Farewell, strong fort hung over them,

Dear to the heart each shining isle,

That seems to smile beneath our ken.

Glen da Roe!

Where the white cherry and garlic blow,

On your blue wave we rocked to sleep,

As on the deep, by Glen da Roe.

Glen Etive!

Whose sunny slopes these waters lave,

The rising sun we seemed to hold,

As in a fold, in Glen Etive.

Glen Masaun

Love to all those who here were born!

Across your peak, at twilight's fall,

The cuckoos call, in Glen Masaun.

Farewell, dear Land,

From Scotland's strand I ne'er had roved

Save at the call of my beloved,

Farewell, dear Land!

The next day they reached the shores of Ireland not fur from the fort of Borrach. And as they landed there, messengers from Borrach met Fergus, saying, "Borrach hath prepared a feast for Conor, and it is Conor's command that the honour of this feast be given to you. Come therefore and spend this night with me; but Conor desires to hasten the sons of Usna that he may welcome them, and he bids them press onward to Armagh this very night."

When Fergus heard that, sudden fear and gloom over shadowed him, lest in very truth Conor had evil designs towards the sons of Usna.

“It was not well done, O Borrach, to offer me a feast in Conor's stead this night, for I was pledged to bring the sons of Usna straight to Armagh without delay."

“It is Conor's command, said Borrach; “needs must a true vassal obey Conor.”

Still was Fergus not keen to stay and he asked Naoise what he ought to do about this.

“Do what they desire of you, O Fergus," said Deirdre, “if to partake of a banquet seems better to you than to protect the sons of Usna. However to me it seems that the lives of your three friends is a good price to pay for a feast."

“I will not forsake them," said Fergus; “for my two sons, Illan the Fair and Buinne the Ruthless Red will be with them to protect them, and my word of honour, moreover, with them; if all the warriors of Ireland were assembled in one place, and all of one mind, they would not be able to break the pledge of Fergus."

"Much thanks we give you for that," said Naoise, for he saw that Fergus feared to fall foul of Conor more than he cared for their safety; “never have we depended on any protection but that of our own right hands alone; we will then go forward to Armagh, and see there if the word of Fergus will be sufficient to protect us."

But Deirdre said: "Go not forward to-night; but let us turn aside, and for t his on e night take shelter with Cú Chulain at Dundalk; then will Fergus have partaken of his feast, and he will be ready to go with you. So will his word be fulfilled and let your lives wil1 be prolonged."

“We think not well of that advice," said Buinne the Ruthless Red; “you have with you the might of your own good hands, and our might, and the plighted word of Fergus to protect you, it is impossible that ye should be betrayed."

“Ah! that plighted word of Fergus'; the man who forsook all for a feast! “ said Deirdre.

“Well may we rely on Fergus ' plighted word."

And she fell into grief and dejection, Alas! Alas!' she cried. “Why left we Scotland of the red deer to come a gain to Ireland? Why put we trust in the light word of Fergus? Woe is come upon us since we listened to the promises of that man! The valiant sons of Usna are destroyed by him, the Lights of Valour of the Gael. Great is my heaviness of heart tonight. Great is the loss that is fallen upon us."

In spite of that the sons of Usna and their two friends went onward towards tne White Cairn of Watching on Sliabh Fuad; but Deirdre was very weary and she lingered behind in the glen and sat down to rest and fell asleep. They did not notice at first that she was not with them, but Naoise found it out and he turned back to seek Deirdre. He found her sitting in the wood on the trunk of a fallen tree, just waking from her sleep. When she saw Naoise she arose and clung to him.

“What happened to you, O fair one? “ said Naoise, “and where fore is your face so wild and fearful, and tears within your eyes? '

"I fell into a sleep, for I was weary," she replied; (t and O Naoise, I fear because of the vision and the dream I saw."

"You are too apt to dream, beloved," said Naoise tenderly, “what was your dream? '”

“Terrible was my dream," said Deirdre; “I saw you, Naoise, and Ainle and Arden, each of my three beloved ones, without a head, your headless bodies lying side by side near Armagh's fort; and Ulan lay there too drenched all with blood, and headless like ye three. But on the other side among our enemies, fighting against us was the treacherous Buinne the Ruthless Red, who now is our protector and our guide; for he had saved his head by treachery to you."

“Sad were your dream indeed," said Naoise, “were it true; but fear it not, it was an empty vision grown out of weariness and pain."

But Deirdre clung yet to him, and she cried, “O Naoise, see, above your head, and o'er the heads of Ainle and of Arden, that sombre cloud of blood! Do you not mark it hanging in the air? All over Armagh lies the heavy pall; but on your head and theirs red blood-drops fall, big, dusky, drenching drops. Let us not go to Armagh." But Naoise thought that from her weariness the mind of Deirdre had become distraught, and all the more he pressed them onward, that she might have rest and shelter for the night.

As they drew near to Armagh, Deirdre said, “One test I give you whether Conor means you good or harm. If into his own house he welcomes you, all will be well, for in his own home would no monarch dare to harm a guest; but if he send you to some other house, while he himself stays on in Armagh's court, then treachery and guile is meant towards you."

Now as they reached the Court of Armagh, messengers came out to meet them from Conor.

“Conor bids you welcome," said the men; “right glad is he that you are come again to Ireland, to your fatherland. But for this one night only is he not prepared to call you as his guests to his own court. To-morrow he will give you audience and bid you to his house. For this one night, then, he bids you turn aside into the Red Branch House, where all is ready for your entertainment."

“It is as I thought," said Deirdre, “Conor means no good to you, I fear."

But Naoise replied, “Where could the Red Branch champions so fitly rest as in the Red Branch House? Most gladly do we seek our hall, to rest and find refreshment for the morrow. We all are travel-stained, but we will bathe and take repose, and on the morrow we will meet Conor."

But when they came to the House of the Red Branch, so weary were they all, that though all kinds of viands were supplied, they ate but little, but lay down to rest. And Naoise said, “Do you remember, Deirdre, how in that last game of draughts we played together, you did win, because we were in Scotland, and my heart was here at home? Now are we back at last, and let us play again; this time I promise I will win from you."

So with the lightsome spirit of a boy, Naoise sat down to play; for now that once again he was at home among his people and in his native land, all thought or dread of evil passed from him. But with Deirdre it was not so, for heavy dread and terror of the morrow lay on her heart, and in her mind she felt that this was their last day of peace and love together.

But in his royal court, Conor grew impatient as he thought that Deirdre was so near at hand, and he not seeing her. “Go now, O foster-mother, to the Red Branch Hall and see if on the child that you did rear reached her early bloom and beauty, and if she still is lovely as when she went from me. If she is still the same, then, in spite of Naoise, I'll have her for my own; but if her bloom is past, then let her be, Naoise may keep her for himself."

Right glad was Leabharcham to get leave to go to Deirdre and to The sons of Usna. Down to the Red Branch House straightway she went, and there were Naoise and her foster-child playing together with the board between them. Now, save Deirdre herself, Naoise was dearer to Leabharcham than any other in the world, and well she knew that her own face and form were upon Deirdre still, only grown riper and more womanly. For, without Conor's knowledge, she oft had gone to seek them when they stayed in Scotland.

Lovingly she kissed them and strong showers of tears sprang from her eyes.

“No good will come to you, ye children of my love," she said with weeping, “that ye are come again with Deirdre here. To-night they practise treachery and ill intent against you all in Armagh. Conor would know if Deirdre is lovely still, and though I tell a lie to shelter her, he will find out, and wreak his vengeance on you for the loss of her. Great evils wait for Armagh and for you, O darling friends. Shut close the doors and guard them well; let no one pass within. Defend yourselves and this sweet damsel here, my foster-child. Trust no man; but repel the attack that surely comes, and victory and blessing be with you."

Then she returned to Armagh; but all along the way she wept quick-gushing showers of tears, and heaved great sighs, for well she knew that from this night the sons of Usna would be alive no more.

What are the tidings that you have for me?” Conor asked. “Good tidings have I, and tidings that are not good."

“Tell me them," said Conor.

“The good tidings that I have are these; that the sons of Usna, the three whose form and figure are best, the three bravest in fight and all deeds of prowess, are come again to Ireland; and, with the Lights of Valour at your side, your enemies will flee before you, as a flock of frightened birds is driven before the gale. The ill-tidings that I have are that through suffering and sorrow the love of my heart and treasure of my soul is changed since she went away, and little of her own bloom and beauty remain upon Deirdre."

“That will do for awhile," said Conor; and he felt his anger abating. But when they had drunk a round or two, he began to doubt the word of Leabharcham.

“O Trendorn," said he to one who sat beside him, “dost you recollect who it was who slew your father? “

"I know well; it was Naoise, son of Usna," he replied. 4 Go you therefore where Naoise is, and see if her own face and form remain upon Deirdre."

So Trendorn went down to the House of the Red Branch, but they had made fast the doors and he could find no way of entrance, for all the gates and windows were stoutly barred. He began to be afraid lest the sons of Usna might be ready to leap out upon him from within, but at last he found a small window which they had forgotten to close, and he put his eye to the window, and saw Naoise and Deirdre still playing at their game peace fully together. Deirdre saw the man looking in at the window, and Naoise, following her eye, caught sight of him also. And he picked up one of the pieces that was lying beside the board, and threw it at Trendorn, so that it struck his eye and tore it out, and in pain and misery the man returned to Armagh.

“You seem not so happy as when you set out, O Trendorn," said Conor; “what has happened to you, and have you seen Deirdre?”

“I have seen her, indeed; I have seen Deirdre, and but that Naoise drove out mine eye I should have been looking at her still, for of all the women of the world, Deirdre is the fairest and the best."

When Conor heard that, he rose up and called his followers together and without a moment's delay they set forward for the house of the Red Branch. For he was filled with jealousy and envy, and he thought the time long until he should get back Deirdre for himself.

“ The pursuit is coming," said Deirdre; “I hear sounds without."

“I will go out and meet them," said Naoise.

“Nay," said Buinne the Ruthless Red, “it was in my hands that my father Fergus placed the sons of Usna to guard them, and it is I who will go forth and fight for them."

“It seems to me," said Deirdre, “that your father hath betrayed the sons of Usna, and it is likely that you would do as your father hath done, O Buinne."

“If my father has been treacherous to you," said Buinne, “it is not I who will do as he has done."

Then he went out and met the warriors of Conor, and put a host of them to the sword.

“Who is this man who is destroying my hosts?“ said Conor.

“Buinne the Ruthless Red, the son of Fergus," say they.

“We bought his father to our side and we must buy the son," said Conor.

He called Buinne and said to him, “I gave a free gift of land to your father Fergus, and I will give a free gift of land to you; come over to my side tonight."

“I will do that," said Buinne, and he went over to the side of Conor.

“Buinne hath deserted you, O sons of Usna, and the son is like the father," Deirdre said.

“He has gone," said Naoise, “but he performed warrior-like deeds before he went."

Then Conor sent fresh warriors down to attack the house.

“The pursuit is coming," said Deirdre.

“I will go out and meet them," said Naoise.

"It is not you who must go, it is I," said Ulan the Fair, son of Fergus, “for to me my father left the charge of you."

“I think the son will be like the father," said Deirdre.

“I am not like to forsake the sons of Usna so long as this hard sword is in my hand," said Ulan the Fair. And the fresh, noble, young hero went out in his battle-array, and valiantly he attacked the host of Conor and made a red rout of them round the house.

“Who is that young warrior who is smiting down my hosts?” said Conor.

“Ulan the Fair, son of Fergus," they reply.

“We will buy him to our side, as his brother was bought," said wily Conor.

So he called Ulan and said, “We gave a possession of land to your father, and another to your brother, and we will give an equal share to you; come over to our side."

But the princely young hero answered: “Your offer, O Conor, will I not accept; for better to me is it to return to my father and tell him that I have kept the charge he laid upon me, than to accept any offer from you, Great Conor."

Then Conor was enraged, and he commanded his own son to attack Ulan, and furiously the two fought together, until Ulan was sore wounded, and he flung his arms into the house, and called on Naoise to do valiantly, for he himself was slain by a son of Conor.

“Ulan has fallen, and you are left alone, said Deirdre, “O sons of Usna."

“He is fallen indeed, said Naoise, “but gallant were the deeds that he per formed before he died."

Then the warriors and mercenaries of Conor drew closer round the house, and they took lighted torches and flung them into the house, and set it on fire. And Naoise lifted Deirdre on his shoulders and raised her on high, and with his brothers on either side, their swords drawn in their hands, they issued forth to fight their way through the press of their enemies. And so terrible were the deeds wrought by those heroes, that Conor feared they would destroy his host. He called his Druids, and said to them, “Work enchantment upon the sons of Usna and turn them back, for no longer do I intend evil against them, but I would bring them home in peace. Noble are the deeds that they have wrought, and I would have them as my servants forever."

The Druids believed the wily Conor and they set to work to weave spells to turn the sons of Usna back to Armagh.

They made a great thick wood before them, through which they thought no man could pass. But without ever stopping to consider their way, the sons of Usna went straight through the wood turning neither to the right hand or the left.

“Good is your enchantment, but it will not avail," said Conor; “the sons of Usna are passing through without the turning of a step, or the bending of a foot. Try some other spell."

Then the Druids made a grey stormy sea before the sons of Usna on the green plain. The three heroes tied their clothing behind their heads, and Naoise set Deirdre again upon his shoulder and went straight on without flinching, without turning back, through the grey shaggy sea, lifting Deirdre on high lest she should wet her feet.

“Your spell is good," said Conor, “yet it does not succeed. The sons of Usna escape my hands. Try another spell."

Then the Druids froze the grey uneven sea into jagged hard lumps of rugged ice, like the sharpness of swords on one side of them and like the stinging of serpents on the other side. Then Arden cried out that he was becoming exhausted and must fain give up.

“Come you, Arden, and rest against my shoulder," said Naoise, “and I will support you."

Arden did so, but it was not long before he died; but though he was dead, Naoise held him up still.

Then Ainle cried out that he could go no longer, for his strength had left him. When Naoise heard that, he heaved a heavy sigh as of one dying of fatigue, but he told Ainle to hold on to him, and he would bring him soon to land. But not long after, the weakness of death came upon Ainle, and his hold relaxed. Naoise looked on either hand and when he saw that his two brothers were dead, he cared not whether he himself should live or die. He heaved a sigh, sore as the sigh of the dying, and his heart broke and he fell dead.

"The sons of Usna are dead now," said the Druids; “but they turned not back."

"Lift up your enchantment," said Conor, “that I now may see the sons of Usna."

Then the Druids lifted the enchantment, and there were the three sons of Usna lying dead, and Deirdre fluttering hither and thither from one to another, weeping bitter heartrending tears. And Conor would have taken her away, but she would not be parted from the sons of Usna, and when their tomb was being dug, Deirdre sat on the edge of the grave, calling on the diggers to dig the pit very broad and smooth. They had dug the pit for three only, and they lowered the bodies of the three heroes into the grave, side by side.

But when Deirdre saw that, she called aloud to the sons of Usna, to make space for her between them, for she was following them. Then the body of Ainle, that was at Naoise's right hand, moved a little apart, and a space was made for Deirdre close at Naoise's side, where she was wont to be, and Deirdre leapt into the tomb, and placed her arm round the neck of Naoise, her own love, and she kissed him, and her heart broke within her and she died; and together in the one tomb the three sons of Usna and Deirdre were buried. And all the men of Ulster who stood by wept aloud.

But Conor was angry, and he ordered the bodies to be uncovered again and the body of Deirdre to be removed, so that even in death she might not be with Naoise. And he caused Deirdre to be buried on one side of the loch, and Naoise on the other side of the loch, and the graves were closed. Then a young pine-tree grew from the grave of Deirdre, and a young pine from the grave of Naoise, and their branches grew towards each other, until they entwined one with the other across the loch. And Conor would have cut them down, but the men of Ulster would not allow this, and they set a watch and protected the trees until Conor died.

Technicolor TMBG

Image by Chris Devers

It might be cool if the iPhone camera were doing these false color "broken Nintendo game" effects intentionally, rather than at random, by surprise, when you least want it to do so. Oh well.

Posted via email to ☛ HoloChromaCinePhotoRamaScope‽: Technicolor TMBG.

• • • • •

Via the Regent Theatre's web site:

A Special Family Show with . . .

They Might Be Giants

Benefit Concerts for Boston By Foot

Sunday, May 23 at 12pm and 3pm

Both shows sold out - thank you!

They Might Be Giants will be performing two special shows especially for families. These are full band, full length performances. Both shows are to benefit Boston By Foot, the non-profit group giving guided walking tours of Boston for over 33 years. All concert goers can also use their ticket stub to get a free tour from Boston by Foot, including Boston by Little Feet tours for kids, during the upcoming season. All profits will go to BBF. http://www.bostonbyfoot.org/

They Might Be Giants Biography

HERE COMES SCIENCE!

For alternative rock legends They Might Be Giants, rave reviews from the likes of Time Magazine, Rolling Stone, The Village Voice, Pitchfork, NPR and beyond might not be that unexpected, but we're not talking about their regular gig here. Sure, TMBG have sold millions of records, are multi-Grammy winners and have even composed a musical accompaniment for an entire issue of McSweeney's, but these most recent accolades are for the work TMBG has created for children and--as the reviews attest--no other band swings as effortlessly from adult music to children’s fare and back again with the artistic and commercial success of They Might Be Giants.

John Flansburgh and John Linnell's latest CD/DVD is Here Comes Science (Idlewild/Disney Sound). It's an ultra-vivid crash course through topics that in lesser hands could easily put kids to sleep. With rock anthems and electronic goodies crafted to amuse, intrigue and deliver the 4-1-1 on evolution, solar system, photosynthesis, the scientific method and more. Following Here Comes the ABCs and Here Come the 123s, Science is geared for older kids and it introduces ideas in a way that not only inform but will stay in your head forever.

While it may seem like an odd move for a duo recognized as the progenitors of the American alternative rock movement, it really all makes perfect sense. From their earliest days with Dial-A-Song through their online music distribution, TMBG have always challenged rock's status quo and gone out of their way to take their music to brand new audiences, and by the looks of things, they’re having a lot of fun doing it their way. The Giants use every bit of fan interactive technology by connecting with kids via regular podcasts and including a DVD of delightful animated interpretations of their songs with each Here Comes... album.

The band is constantly working on new music, new projects and touring--sometimes with 2 shows a day. Founders John Flansburgh and John Linnell, along with their long standing live combo of Dan Miller, Danny Weinkauf and Marty Beller, show no signs of swapping one successful gig (adult music) for another (children’s music). Rejoice people of Earth--there’s just that much more for us all to enjoy.

Question: You once said in an interview that TMBGs knew what you didn’t want to do with your music geared for kids: You didn’t want to tell them how to behave or write songs that are educational. But these songs are quite educational, and in fact, you have a science consultant on this record. Did you make a conscious decision to really teach something on Here Comes Science?

John Linnell: I think it’s still a record you can listen to for enjoyment, and that’s real important to us. I am perfectly comfortable with the idea of something that is pure entertainment, but I don’t think there is any need for something just purely educational from us. My sense of this record is that it is mostly fun, musical and interesting and it happens to have lyrics that talk about science.

Question: Did any Children’s books or albums make an impression on you when you were a child? Because now you’re making that impression on children.

John Flansburgh: We get that question a lot, and it’s a valid question, but speaking for myself, I feel like we have something to contribute to kid's music because what we're doing is actually lacking in the general culture. Generally, our stuff is not really coming out of any amazing experience with the kid's stuff from the past. Our childhood was during the really golden era of classic pop and singles. Those songs weren't really designed for kids, but the power of it spoke to us and a lot of other kids quite directly.

Curiously--although I see the obvious connections--we didn’t really grow up with all of the progressive kids stuff of the 70's. We were that micro generation of glitter-rock young teens listening to Alice Cooper and David Bowie and we totally missed the boat on Sesame Street and School House Rock and Free To Be You and Me. But even being a bit too old for it, you could tell there was something cool about that stuff. Basically the cartoons of our generation were either super-violent, like Spiderman, or the really simple-minded Hanna-Barbera cartoons.

Question: Which one of you was the science student? Either or you? Neither of you?

J. Linnell: Specifically into science? I would say we were both middling students in school, but philosophically we are both, as adults, very pro-science. We like living in the post-enlightenment era in history. Are we still living in the enlightenment or is it over now, I can’t tell? Are we in the “en-darkenment” now?

J. Flansburgh: I think we’re actually in to the “gee whiz” part of science--all the scientific phenomenon that sparks your imagination. We certainly aren't academics, but there is something remarkable about the world of science and there are ideas in science that just send your mind reeling.

J. Linnell: One the things that is exciting about it is that it makes you realize that things that are true, that can be proven, aren’t always intuitive. There is a difference between what seems to be the case and what turns out to be proven to be the case, and that’s really exciting. The world isn’t always what it seems to be and it makes everything more wonderful in a way. You have an experience of the world, walking around, and then science provides knowledge about the world that is not always anything like the experience.

The history of scientific discovery is partly revealing things that you don’t always experience directly, it’s bizarre in a way that so much of what we know is stuff we can’t always experience directly, like molecules and galaxies.

Question: Does that make it easier or harder to write about Science?

J. Linnell: Well, both. There is a point that you do reflect that you’re trying to explain something preposterous. And luckily, I think kids know the whole world is strange and preposterous, but as they get older, they get used to the idea that there are facts they just have to take someone’s word for.

Question: Considering you guys once used an answering machine to showcase your material, how amazed are you that you have all of this media at your disposal – podcasts, internet, video, etc…how has it changed the way you work?

J. Flansburgh: We enjoyed having an easy-breezy, loose reputation in terms of getting our music out to people. It was very great to be the one of the few acts in the United States who wasn’t preoccupied with getting on the radio or a cash return on our music. Of course now there is almost no end to the free stuff, and it is cool to see how much you can get in to the world, but with the most popular videos on YouTube being cats jumping into a box or people getting pushed down escalators, part of me worries that all this electronic media is just in the service of turning our culture into an endless episode of America’s Funniest Home Videos.

J. Linnell: A lot of what the technology suggests to people is the democratizing of culture and the notion of interactivity kind of caught fire online early on. What’s weird for John and I is that we were never interested in either one of those things. We actually like the idea of controlling what we are doing and we like the old fashioned idea of there being quality control on culture, that you would get the “good stuff” and there would be a way, through a critical apparatus or institutions, that would deliver the good stuff and filter out the bad stuff. It feels like the big problem nowadays is that everything should be available to everyone at all times and the result is a lot of garbage to wade through…not to sound like an 80 year old man! (laughs)

Question: With your accompanying DVD, how did the directors and animators come together? Are they the same people from Here Come the 123s? How much creative control do you give the animators with your songs?

J. Flansburgh: We are the producers on all the animated material and we select the artists we collaborate with pretty carefully. We've been involved in a lot of television and video projects over the years and that was very good training for these projects. There is an expression in rock video production: “Good. Fast. Cheap. Choose two” It’s a very unreasonable thing to expect everything to come together on a tight budget. Our strategy is to give the animators a relatively long lead time so they can do something that will be a good portfolio piece for them and something cool for us. And although we’re on a tight budget, we can offer a large amount of artistic freedom, and that gives us the opportunity to work with the most creative people out there.

Question: For this tour, you’re doing both “kid” and “adult” shows, sometimes 2 in one day. How is it different when you perform in front of kids versus when you perform in front of adults?

J. Flansburgh: Whatever pretensions you might have about your performance get totally re-calibrated when you’re playing for kids–playing a kid show is probably a bit closer to being a school teacher than being a rock star. There are also a lot of parents in the audience and we address them as well which kind of breaks forth the wall of "kiddie-ness."

Just to address the questions we always get: “how is it different writing a song for kids or writing for adults?” or “performing for kids and performing for adults?” Well, there is a real overlap, but there are meaningful differences too. A good song works in a way that is kind of irreducible whether or not it’s for kids or adults. If a song has a strong melody or an interesting concept, it will animate any audience, but in performance, kids have a really short attention span, so keeping things moving is important. Routinely the confetti machine gets the biggest response of the day. That will keep your ego in check.

Although in the past, “Clap your Hands” and "Alphabet of Nations" worked for adults, by and large the kid stuff stayed in the kid show just because it's, well, for kids! (laughs). But with "Here Comes Science" a lot of the songs work good in the adult show. and that’s unusual. “Meet the Elements,” “My Brother the Ape,” “A Shooting Star is not a Star,” and “Why Does the Sun Shine” slid into the adult show without any second thoughts, and “I Am a Paleontologist” is totally rocking live.

Question: What’s next for They Might Be Giants?

J. Flansburgh: We’re working on a rock album right now, but we have so much touring interrupting our effort it's hard to know when it will get done, so the real answer is we're going to be spending a lot of time on a tour bus trying to figure out how to get the WiFi working!

Our children’s book collaboration with Pascal Campion, Kids Go, just came out at the end of last year on Simon & Schuster. It's actually a very beautiful project and a fulfillment of a dream of mine. When we were approached, I wanted to do an actual picture book, which very few people get to do, and it was exciting to realize that dream. A good picture book is something that really stays with you.

Technicolor TMBG

Image by Chris Devers

It might be cool if the iPhone camera were doing these false color "broken Nintendo game" effects intentionally, rather than at random, by surprise, when you least want it to do so. Oh well.

Posted via email to ☛ HoloChromaCinePhotoRamaScope‽: Technicolor TMBG.

• • • • •

Via the Regent Theatre's web site:

A Special Family Show with . . .

They Might Be Giants

Benefit Concerts for Boston By Foot

Sunday, May 23 at 12pm and 3pm

Both shows sold out - thank you!

They Might Be Giants will be performing two special shows especially for families. These are full band, full length performances. Both shows are to benefit Boston By Foot, the non-profit group giving guided walking tours of Boston for over 33 years. All concert goers can also use their ticket stub to get a free tour from Boston by Foot, including Boston by Little Feet tours for kids, during the upcoming season. All profits will go to BBF. http://www.bostonbyfoot.org/

They Might Be Giants Biography

HERE COMES SCIENCE!

For alternative rock legends They Might Be Giants, rave reviews from the likes of Time Magazine, Rolling Stone, The Village Voice, Pitchfork, NPR and beyond might not be that unexpected, but we're not talking about their regular gig here. Sure, TMBG have sold millions of records, are multi-Grammy winners and have even composed a musical accompaniment for an entire issue of McSweeney's, but these most recent accolades are for the work TMBG has created for children and--as the reviews attest--no other band swings as effortlessly from adult music to children’s fare and back again with the artistic and commercial success of They Might Be Giants.

John Flansburgh and John Linnell's latest CD/DVD is Here Comes Science (Idlewild/Disney Sound). It's an ultra-vivid crash course through topics that in lesser hands could easily put kids to sleep. With rock anthems and electronic goodies crafted to amuse, intrigue and deliver the 4-1-1 on evolution, solar system, photosynthesis, the scientific method and more. Following Here Comes the ABCs and Here Come the 123s, Science is geared for older kids and it introduces ideas in a way that not only inform but will stay in your head forever.

While it may seem like an odd move for a duo recognized as the progenitors of the American alternative rock movement, it really all makes perfect sense. From their earliest days with Dial-A-Song through their online music distribution, TMBG have always challenged rock's status quo and gone out of their way to take their music to brand new audiences, and by the looks of things, they’re having a lot of fun doing it their way. The Giants use every bit of fan interactive technology by connecting with kids via regular podcasts and including a DVD of delightful animated interpretations of their songs with each Here Comes... album.

The band is constantly working on new music, new projects and touring--sometimes with 2 shows a day. Founders John Flansburgh and John Linnell, along with their long standing live combo of Dan Miller, Danny Weinkauf and Marty Beller, show no signs of swapping one successful gig (adult music) for another (children’s music). Rejoice people of Earth--there’s just that much more for us all to enjoy.

Question: You once said in an interview that TMBGs knew what you didn’t want to do with your music geared for kids: You didn’t want to tell them how to behave or write songs that are educational. But these songs are quite educational, and in fact, you have a science consultant on this record. Did you make a conscious decision to really teach something on Here Comes Science?

John Linnell: I think it’s still a record you can listen to for enjoyment, and that’s real important to us. I am perfectly comfortable with the idea of something that is pure entertainment, but I don’t think there is any need for something just purely educational from us. My sense of this record is that it is mostly fun, musical and interesting and it happens to have lyrics that talk about science.

Question: Did any Children’s books or albums make an impression on you when you were a child? Because now you’re making that impression on children.

John Flansburgh: We get that question a lot, and it’s a valid question, but speaking for myself, I feel like we have something to contribute to kid's music because what we're doing is actually lacking in the general culture. Generally, our stuff is not really coming out of any amazing experience with the kid's stuff from the past. Our childhood was during the really golden era of classic pop and singles. Those songs weren't really designed for kids, but the power of it spoke to us and a lot of other kids quite directly.

Curiously--although I see the obvious connections--we didn’t really grow up with all of the progressive kids stuff of the 70's. We were that micro generation of glitter-rock young teens listening to Alice Cooper and David Bowie and we totally missed the boat on Sesame Street and School House Rock and Free To Be You and Me. But even being a bit too old for it, you could tell there was something cool about that stuff. Basically the cartoons of our generation were either super-violent, like Spiderman, or the really simple-minded Hanna-Barbera cartoons.

Question: Which one of you was the science student? Either or you? Neither of you?

J. Linnell: Specifically into science? I would say we were both middling students in school, but philosophically we are both, as adults, very pro-science. We like living in the post-enlightenment era in history. Are we still living in the enlightenment or is it over now, I can’t tell? Are we in the “en-darkenment” now?

J. Flansburgh: I think we’re actually in to the “gee whiz” part of science--all the scientific phenomenon that sparks your imagination. We certainly aren't academics, but there is something remarkable about the world of science and there are ideas in science that just send your mind reeling.

J. Linnell: One the things that is exciting about it is that it makes you realize that things that are true, that can be proven, aren’t always intuitive. There is a difference between what seems to be the case and what turns out to be proven to be the case, and that’s really exciting. The world isn’t always what it seems to be and it makes everything more wonderful in a way. You have an experience of the world, walking around, and then science provides knowledge about the world that is not always anything like the experience.

The history of scientific discovery is partly revealing things that you don’t always experience directly, it’s bizarre in a way that so much of what we know is stuff we can’t always experience directly, like molecules and galaxies.

Question: Does that make it easier or harder to write about Science?

J. Linnell: Well, both. There is a point that you do reflect that you’re trying to explain something preposterous. And luckily, I think kids know the whole world is strange and preposterous, but as they get older, they get used to the idea that there are facts they just have to take someone’s word for.

Question: Considering you guys once used an answering machine to showcase your material, how amazed are you that you have all of this media at your disposal – podcasts, internet, video, etc…how has it changed the way you work?

J. Flansburgh: We enjoyed having an easy-breezy, loose reputation in terms of getting our music out to people. It was very great to be the one of the few acts in the United States who wasn’t preoccupied with getting on the radio or a cash return on our music. Of course now there is almost no end to the free stuff, and it is cool to see how much you can get in to the world, but with the most popular videos on YouTube being cats jumping into a box or people getting pushed down escalators, part of me worries that all this electronic media is just in the service of turning our culture into an endless episode of America’s Funniest Home Videos.

J. Linnell: A lot of what the technology suggests to people is the democratizing of culture and the notion of interactivity kind of caught fire online early on. What’s weird for John and I is that we were never interested in either one of those things. We actually like the idea of controlling what we are doing and we like the old fashioned idea of there being quality control on culture, that you would get the “good stuff” and there would be a way, through a critical apparatus or institutions, that would deliver the good stuff and filter out the bad stuff. It feels like the big problem nowadays is that everything should be available to everyone at all times and the result is a lot of garbage to wade through…not to sound like an 80 year old man! (laughs)

Question: With your accompanying DVD, how did the directors and animators come together? Are they the same people from Here Come the 123s? How much creative control do you give the animators with your songs?

J. Flansburgh: We are the producers on all the animated material and we select the artists we collaborate with pretty carefully. We've been involved in a lot of television and video projects over the years and that was very good training for these projects. There is an expression in rock video production: “Good. Fast. Cheap. Choose two” It’s a very unreasonable thing to expect everything to come together on a tight budget. Our strategy is to give the animators a relatively long lead time so they can do something that will be a good portfolio piece for them and something cool for us. And although we’re on a tight budget, we can offer a large amount of artistic freedom, and that gives us the opportunity to work with the most creative people out there.

Question: For this tour, you’re doing both “kid” and “adult” shows, sometimes 2 in one day. How is it different when you perform in front of kids versus when you perform in front of adults?

J. Flansburgh: Whatever pretensions you might have about your performance get totally re-calibrated when you’re playing for kids–playing a kid show is probably a bit closer to being a school teacher than being a rock star. There are also a lot of parents in the audience and we address them as well which kind of breaks forth the wall of "kiddie-ness."

Just to address the questions we always get: “how is it different writing a song for kids or writing for adults?” or “performing for kids and performing for adults?” Well, there is a real overlap, but there are meaningful differences too. A good song works in a way that is kind of irreducible whether or not it’s for kids or adults. If a song has a strong melody or an interesting concept, it will animate any audience, but in performance, kids have a really short attention span, so keeping things moving is important. Routinely the confetti machine gets the biggest response of the day. That will keep your ego in check.

Although in the past, “Clap your Hands” and "Alphabet of Nations" worked for adults, by and large the kid stuff stayed in the kid show just because it's, well, for kids! (laughs). But with "Here Comes Science" a lot of the songs work good in the adult show. and that’s unusual. “Meet the Elements,” “My Brother the Ape,” “A Shooting Star is not a Star,” and “Why Does the Sun Shine” slid into the adult show without any second thoughts, and “I Am a Paleontologist” is totally rocking live.

Question: What’s next for They Might Be Giants?

J. Flansburgh: We’re working on a rock album right now, but we have so much touring interrupting our effort it's hard to know when it will get done, so the real answer is we're going to be spending a lot of time on a tour bus trying to figure out how to get the WiFi working!

Our children’s book collaboration with Pascal Campion, Kids Go, just came out at the end of last year on Simon & Schuster. It's actually a very beautiful project and a fulfillment of a dream of mine. When we were approached, I wanted to do an actual picture book, which very few people get to do, and it was exciting to realize that dream. A good picture book is something that really stays with you.

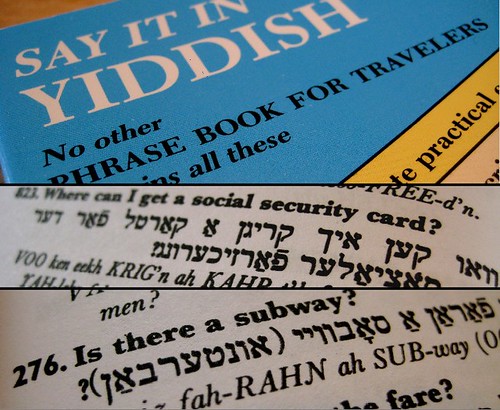

Tsee iz fahran ah Subway?

Image by angus mcdiarmid

Michael Chabon calls it "Probably the saddest book I own", and Ellen got me it for my birthday.

Chabon talks about it in his essay, "A Yiddish Pale Fire", which I read a few years ago and have ever since felt compelled to mention in practically any discussion that touches in any way on Jews, Israel or language. I was very impressed. It's the best thing I've read by Chabon (better than his novel The Yiddish Policemen's Union, which is where the train of thought in the essay eventually ended up), and one of the most interesting and moving essays I've ever read. I've pasted it below, as Chabon has discontinued his website, where it used to live. Print it out and read it later on!

Chabon's right: there's something incredibly sad and strange about the phrasebook. It's part of a genuine series of phrasebooks, all designed to be used by travellers in various countries. But in what particular country would you need to ask, in Yiddish, where to get a social security card? As Chabon says, "At what time in the history of the world was there a place ... where not only the doctors and waiters and trolley conductors spoke Yiddish, but also the airline clerks, travel agents, ferry captains, and casino employees?"

Chabon goes on to imagine a few possible worlds in which this phrasebook might be an essential part of a traveller's luggage, each more heartbreaking than the last. It's interesting that he chose the second of his imagined worlds -- the one in which Jews were settled in Alaska, not Palestine, after the second world war, and the state became "a kind of Jewish Sweden, social-democratic, resource rich, prosperous" -- as the setting for The Yiddish Policemen's Union, rather than the one that he finally thinks of (which I won't spoil by talking about here).

So, read it, already!

-----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

A Yiddish Pale Fire

by Michael Chabon

Probably the saddest book that I own is a copy of Say It In Yiddish, edited by Uriel and Beatrice Weinreich, and published by Dover. I got it new, in 1993, but the book was originally brought out in 1958. It's part of a series, according to the back cover, with which I'm otherwise unfamiliar, the Dover "Say It" books. I've never seen Say It In Swahili, Say It In Hindi, or Say It In Serbo-Croatian, nor have I ever been to any of the countries where one of them might come in handy. As for the country in which I'd do well to have a copy of Say It In Yiddish in my pocket, naturally I've never been there either. I don't believe that anyone has.

When I first came across Say It In Yiddish, on a shelf in a big chain store in Orange County, California, I couldn't quite believe that it was real. There was only one copy of it, buried in the languages section at the bottom of the alphabet. It was like a book in a story by J. L Borges, unique, inexplicable, possibly a hoax. The first thing that really struck me about it was, paradoxically, its unremarkableness, the conventional terms with which Say It In Yiddish advertises itself on its cover. "No other PHRASE BOOK FOR TRAVELLERS," it claims, "contains all these essential features." It boasts of "Over 1,600 up-to-date practical entries" (up-to-date!), "easy pronunciation transcription," and a "sturdy binding--pages will not fall out."

Inside, Say It In Yiddish delivers admirably on all the bland promises made by the cover. Virtually every eventuality, calamity, chance or circumstance, apart from the amorous, that could possibly befall the traveller is covered, under general rubrics like "Shopping," "Barber Shop and Beauty Parlor," "Appetizers," "Difficulties," with each of the over sixteen hundred up-to-date practical entries numbered, from 1, "yes," to 1611, "the zipper," a tongue-twister Say It In Yiddish renders, in roman letters, as BLITS-shleh-s'l. There are words and phrases to get the traveler through a visit to the post office to buy stamps in Yiddish, and through a visit to the doctor to take care of that krahmpf (1317) after one has eaten too much of the LEH-ber mit TSIB-eh-less (620) served at the cheap res-taw-RAHN (495) just down the EH-veh-new (197) from one's haw-TEL (103).

One possible explanation of at least part of the absurd poignance of Say It In Yiddish presents itself: that its list of words and phrases is standard throughout the "Say It" series. Once we accept the proposition of a modern Yiddish phrase book, Yiddish versions of such phrases as "Where can I get a social security card?" and "Can you help me jack up the car?", taken in the context of the book's part of a uniform series, become more understandable. But an examination of the specific examples chosen for inclusion under the various, presumably standard, rubrics reveals that the Weinreichs have indeed served as editors here, considering their supposedly useful phrases with care, selecting, for example, to give Yiddish translations for the English names of the following foods, none of them very likely to be found under "Food" in the Swahili, Japanese, or Malay books in the series: stuffed cabbage, kreplach, blintzes, matzo, lox, corned beef, herring, kugel, tsimmis, and schav. The fact that most of these words do not seem to require much work to get them into Yiddish suggests that Say It In Yiddish has been edited with a particular kind of reader in mind, the reader who is traveling, or plans to travel, to a very particular kind of place, a place where one can expect to find both ahn OON-tehr-bahn (subway) and geh-FIL-teh FISH."

What were they thinking, the Weinreichs? Was the original 1958 Dover edition simply the reprint of some earlier, less heartbreakingly implausible book? At what time in the history of the world was there a place of the kind that the Weinreichs imply, a place where not only the doctors and waiters and trolley conductors spoke Yiddish, but also the airline clerks, travel agents, ferry captains, and casino employees? A place where you could rent a summer home from Yiddish speakers, go to a Yiddish movie, get a finger wave from a Yiddish-speaking hairstylist, a shoeshine from a Yiddish-speaking shineboy, and then have your dental bridge repaired by a Yiddish-speaking dentist? If, as seems likelier, the book first saw light in 1958, a full ten years after the founding of the country that turned its back once and for all on the Yiddish language, condemning it to watch the last of its native speakers die one by one in a headlong race for extinction with the twentieth century itself, then the tragic dimension of the joke looms larger, and makes the Weinreichs' intention even harder to divine. It seems an entirely futile effort on the part of its authors, a gesture of embittered hope, of valedictory daydreaming, of a utopian impulse turned cruel and ironic.

The Weinreichs have laid out, with numerical precision, the outlines of a world, of a fantastic land in which it would behoove you to know how to say, in Yiddish,

250. What is the flight number?

1372. I need something for a tourniquet.

1379. Here is my identification.

254. Can I go by boat/ferry to----?

The blank in the last of those phrases, impossible to fill in, tantalizes me. Whither could I sail on that boat/ferry, in the solicitous company of Uriel and Beatrice Weinreich, and from what shore?

I dream of two possible destinations. The first might be a modern independent state very closely analogous to the State of Israel--call it the State of Yisroel--a postwar Jewish homeland created during a time of moral emergency, located presumably, but not necessarily, in Palestine; it could be in Alaska, or on Madagascar. Here, perhaps, that minority faction of the Zionist movement who favored the establishment of Yiddish as the national language of the Jews were able to prevail over their more numerous Hebraist opponents. There is Yiddish on the money, of which the basic unit is the herzl, or the dollar, or even the zloty. There are Yiddish color commentators for soccer games, Yiddish-speaking cash machines, Yiddish tags on the collars of dogs. Public debate, private discourse, joking and lamentation, all are conducted not in a new-old, partly artificial language like Hebrew, a prefabricated skyscraper still under construction, with only the lowermost of its stories as yet inhabited by the generations, but in a tumbledown old palace capable in the smallest of its stones (the word nu) of expressing slyness, tenderness, derision, romance, disputation, hopefulness, skepticism, sorrow, a lascivious impulse, or the confirmation of one's worst fears.

The implications of this change in the official language of the "Jewish homeland," a change which, depending on your view of human character and its underpinnings, is either minor or fundamental, are difficult to sort out. I can't help thinking that such a nation, speaking its essentially European tongue, would, in the Middle East, stick out among its neighbors to an even greater degree than Israel does now. But would the Jews of a Mediterranean Yisroel be impugned and admired for having the same kind of character that Israelis, rightly or wrongly, are widely taken to have, the classic sabra personality: rude, scrappy, loud, tough, secular, hard-headed, cagey, pushy? Is it living in a near-permanent state of war, or is it the Hebrew language, or something else, that has made Israeli humor so dark, so barbed, so cynical, so untranslatable? Perhaps this Yisroel, like its cognate in our own world, has the potential to seem a frightening, even a harrowing place, as the following sequence, from the section on "Difficulties," seems to imply:

109. What is the matter here?

110. What am I to do?

112. They are bothering me.

113. Go away.

114. I will call a policeman.

I can imagine another Yisroel, the youngest nation on the North American continent, founded in the former Alaska Territory during World War II as a resettlement zone for the Jews of Europe. (For a brief while, I once read, Franklin Roosevelt was nearly sold on such a plan.) Perhaps after the war, in this Yisroel, the millions of immigrant Polish, Rumanian, Hungarian, Lithuanian, Austrian, Czech and German Jews held a referendum, and chose independence over proferred statehood in the U.S. The resulting country is obviously a far different place than Israel. It is a cold, northern land of furs, paprika, samovars and one long, glorious day of summer. The portraits on those postage stamps we buy are of Walter Benjamin, Simon Dubnow, Janusz Korczak, and of a hundred Jews unknown to us, whose greatness was allowed to flower only here, in this world. It would be absurd to speak Hebrew, that tongue of spikenard and almonds, in such a place. This Yisroel--or maybe it would be called Alyeska--is a kind of Jewish Sweden, social-democratic, resource rich, prosperous, organizationally and temperamentally far more akin to its immediate neighbor, Canada, then to its more freewheeling benefactor far to the south. Perhaps, indeed, there has been some conflict, in the years since independence, between the United States and Alyeska. Perhaps oilfields have been seized, fishing vessels boarded. Perhaps not all of the native peoples were happy with the outcome of Roosevelt's humanitarian policies and the treaty of 1948." Lately there may have been a few problems assimilating the Jews of Quebec, in flight from the ongoing separatist battles there.

This country of the Weinreichs is in the nature of a wistful fantasyland, a toy theater with miniature sets and furnishings to arrange and rearrange, painted backdrops on which the gleaming lineaments of a snowy Jewish Onhava can be glimpsed, all its grief concealed behind the scrim, hidden in the machinery of the loft, sealed up beneath trap doors in the floorboards. But grief haunts every mile of that other destination to which the Weinreichs beckon, unwittingly perhaps but in all the awful detail that Dover's "Say It" series requires. Grief hand-colors all the postcards, stamps the passports, sours the cooking, fills the luggage. It keens all night in the pipes of old hotels. The Weinreichs are taking us home, to the "old country." To Europe.

In this Europe the millions of Jews who were never killed produced grand-children, and great-grandchildren, and great-great-grandchildren. The countryside retains large pockets of country people whose first language is still Yiddish, and in the cities there are many more for whom Yiddish is the language of kitchen and family, of theater and poetry and scholarship. A surprisingly large number of these people are my relations. I can go visit them, the way Irish Americans I know are always visiting second and third cousins in Galway or Cork, sleeping in their strange beds, eating their strange food, and looking just like them. Imagine. Perhaps one of my cousins might take me to visit the house where my father's mother was born, or to the school in Vilna that my grandfather's grandfather attended with the boy Abraham Cahan. For my relatives, though they will doubtless know at least some English, I will want to trot out a few appropriate Yiddish phrases, more than anything as a way of reestablishing the tenuous connection between us; in this world Yiddish is not, as it is in ours, a tin can with no tin can on the other end of the string. Here, though I can get by without them, I will be glad to have the Weinreichs along. Who knows but that visting some remote Polish backwater I may be compelled to visit a dentist to whom I will want to cry out, having found the appropriate number (1447), eer TOOT meer VAY!

What is this Europe like, with its twenty-five, thirty, or thirty-five million Jews? Are they tolerated, despised, ignored by, or merely indistinguishable from their fellow modern Europeans? What is the world like, never having felt the need to create an Israel, that hard bit of grit in the socket that hinges Africa to Asia?

What does it mean to originate from a place, from a world, from a culture that no longer exists, and from a language that may die in this generation? What phrases would I need to know in order to speak to those millions of unborn phantoms to whom I belong?

Just what am I supposed to do with this book?

(c) Michael Chabon

Sibiu Cathedral (Angelic Host)

Image by Fergal of Claddagh

The Rejection of the Enlightenment and the Resurrection of the Sublime

THE SUBLIME AND THE BEAUTIFUL

Kant's category of the sublime; (das Erhabene)

It was certainly never Kant's idea that his idea of the sublime would one day be used by post-modernists to delve deeper into their selective incorporation of Nietzsche's idea of aesthetics. Lyotard regarded himself as far removed from Kant, as the world had moved from deep reflection to competition on the market.

Kant described the experience of the beautiful as "pleasure without any practical interest whatsoever." The delight in art is purely a pleasure, it bears no reference to its commercial value nor is it influenced by knowledge of its archaeological background, nor does its ethical background (except maybe in Greek Tragedy), have any effect on us. Art is reduced to subjective enjoyment, a rose garden may be beautiful and experienced as so; if the practical consideration of the rose garden as part of an eco-system is invoked then it is not enjoyed as purely artistic. To enjoy art there should be no concise conceptual understanding, there should be a free play of the imagination.

The notion of the sublime, adopted from pseudo-Longinus, was popular in 17th c. Europe. In England there was also an interest in the beautiful (the majesty of the brute forces of nature [Burke]). Kant then transposes the aesthetics of the infinite (the Sublime) into his transcendental method of philosophy. He does not give reason a large role in this process. In his consideration of the Sublime he discovers how the free interplay of the sensuous Einbildungskraft (imagination), relates to speculative Vernunf (reason - which deals with ideas of the infinite).

Natural beauty carries a purposiveness in its form, by which the object somehow seems predestined for our judgement; whereas that which in us gives rise to the feeling of sublimity may in its form appear to oppose our purposive judgement, to be inadequate to our power of representation -in a sense to do violence to our imagination. Yet, in spite of this, it is judged to be the more sublime.