Army Photography Contest - 2004 - FMWRC - Arts and Crafts - SFOR Surveillance

Image by familymwr

Photo by Master Sgt. Craig Lifton

To learn more about the annual U.S. Army Photography Competition, visit us online at www.armymwr.com

U.S. Army Arts and Crafts History

After World War I the reductions to the Army left the United States with a small force. The War Department faced monumental challenges in preparing for World War II. One of those challenges was soldier morale. Recreational activities for off duty time would be important. The arts and crafts program informally evolved to augment the needs of the War Department.

On January 9, 1941, the Secretary of War, Henry L. Stimson, appointed Frederick H. Osborn, a prominent U.S. businessman and philanthropist, Chairman of the War Department Committee on Education, Recreation and Community Service.

In 1940 and 1941, the United States involvement in World War II was more of sympathy and anticipation than of action. However, many different types of institutions were looking for ways to help the war effort. The Museum of Modern Art in New York was one of these institutions. In April, 1941, the Museum announced a poster competition, “Posters for National Defense.” The directors stated “The Museum feels that in a time of national emergency the artists of a country are as important an asset as men skilled in other fields, and that the nation’s first-rate talent should be utilized by the government for its official design work... Discussions have been held with officials of the Army and the Treasury who have expressed remarkable enthusiasm...”

In May 1941, the Museum exhibited “Britain at War”, a show selected by Sir Kenneth Clark, director of the National Gallery in London. The “Prize-Winning Defense Posters” were exhibited in July through September concurrently with “Britain at War.” The enormous overnight growth of the military force meant mobilization type construction at every camp. Construction was fast; facilities were not fancy; rather drab and depressing.

In 1941, the Fort Custer Army Illustrators, while on strenuous war games maneuvers in Tennessee, documented the exercise The Bulletin of the Museum of Modern Art, Vol. 9, No. 3 (Feb. 1942), described their work. “Results were astonishingly good; they showed serious devotion ...to the purpose of depicting the Army scene with unvarnished realism and a remarkable ability to capture this scene from the soldier’s viewpoint. Civilian amateur and professional artists had been transformed into soldier-artists. Reality and straightforward documentation had supplanted (replaced) the old romantic glorification and false dramatization of war and the slick suavity (charm) of commercial drawing.”

“In August of last year, Fort Custer Army Illustrators held an exhibition, the first of its kind in the new Army, at the Camp Service Club. Soldiers who saw the exhibition, many of whom had never been inside an art gallery, enjoyed it thoroughly. Civilian visitors, too, came and admired. The work of the group showed them a new aspect of the Army; there were many phases of Army life they had never seen or heard of before. Newspapers made much of it and, most important, the Army approved. Army officials saw that it was not only authentic material, but that here was a source of enlivenment (vitalization) to the Army and a vivid medium for conveying the Army’s purposes and processes to civilians and soldiers.”

Brigadier General Frederick H. Osborn and War Department leaders were concerned because few soldiers were using the off duty recreation areas that were available. Army commanders recognized that efficiency is directly correlated with morale, and that morale is largely determined from the manner in which an individual spends his own free time. Army morale enhancement through positive off duty recreation programs is critical in combat staging areas.

To encourage soldier use of programs, the facilities drab and uninviting environment had to be improved. A program utilizing talented artists and craftsmen to decorate day rooms, mess halls, recreation halls and other places of general assembly was established by the Facilities Section of Special Services. The purpose was to provide an environment that would reflect the military tradition, accomplishments and the high standard of army life. The fact that this work was to be done by the men themselves had the added benefit of contributing to the esprit de corps (teamwork, or group spirit) of the unit.

The plan was first tested in October of 1941, at Camp Davis, North Carolina. A studio workshop was set up and a group of soldier artists were placed on special duty to design and decorate the facilities. Additionally, evening recreation art classes were scheduled three times a week. A second test was established at Fort Belvoir, Virginia a month later. The success of these programs lead to more installations requesting the program.

After Pearl Harbor was bombed, the Museum of Modern Art appointed Mr. James Soby, to the position of Director of the Armed Service Program on January 15, 1942. The subsequent program became a combination of occupational therapy, exhibitions and morale-sustaining activities.

Through the efforts of Mr. Soby, the museum program included; a display of Fort Custer Army Illustrators work from February through April 5, 1942. The museum also included the work of soldier-photographers in this exhibit. On May 6, 1942, Mr. Soby opened an art sale of works donated by museum members. The sale was to raise funds for the Soldier Art Program of Special Services Division. The bulk of these proceeds were to be used to provide facilities and materials for soldier artists in Army camps throughout the country.

Members of the Museum had responded with paintings, sculptures, watercolors, gouaches, drawings, etchings and lithographs. Hundreds of works were received, including oils by Winslow Homer, Orozco, John Kane, Speicher, Eilshemius, de Chirico; watercolors by Burchfield and Dufy; drawings by Augustus John, Forain and Berman, and prints by Cezanne, Lautrec, Matisse and Bellows. The War Department plan using soldier-artists to decorate and improve buildings and grounds worked. Many artists who had been drafted into the Army volunteered to paint murals in waiting rooms and clubs, to decorate dayrooms, and to landscape grounds. For each artist at work there were a thousand troops who watched. These bystanders clamored to participate, and classes in drawing, painting, sculpture and photography were offered. Larger working space and more instructors were required to meet the growing demand. Civilian art instructors and local communities helped to meet this cultural need, by providing volunteer instruction and facilities.

Some proceeds from the Modern Museum of Art sale were used to print 25,000 booklets called “Interior Design and Soldier Art.” The booklet showed examples of soldier-artist murals that decorated places of general assembly. It was a guide to organizing, planning and executing the soldier-artist program. The balance of the art sale proceeds were used to purchase the initial arts and crafts furnishings for 350 Army installations in the USA.

In November, 1942, General Somervell directed that a group of artists be selected and dispatched to active theaters to paint war scenes with the stipulation that soldier artists would not paint in lieu of military duties.

Aileen Osborn Webb, sister of Brigadier General Frederick H. Osborn, launched the American Crafts Council in 1943. She was an early champion of the Army program.

While soldiers were participating in fixed facilities in the USA, many troops were being shipped overseas to Europe and the Pacific (1942-1945). They had long periods of idleness and waiting in staging areas. At that time the wounded were lying in hospitals, both on land and in ships at sea. The War Department and Red Cross responded by purchasing kits of arts and crafts tools and supplies to distribute to “these restless personnel.” A variety of small “Handicraft Kits” were distributed free of charge. Leathercraft, celluloid etching, knotting and braiding, metal tooling, drawing and clay modeling are examples of the types of kits sent.

In January, 1944, the Interior Design Soldier Artist program was more appropriately named the “Arts and Crafts Section” of Special Services. The mission was “to fulfill the natural human desire to create, provide opportunities for self-expression, serve old skills and develop new ones, and assist the entire recreation program through construction work, publicity, and decoration.”

The National Army Art Contest was planned for the late fall of 1944. In June of 1945, the National Gallery of Art in Washington D.C., for the first time in its history opened its facilities for the exhibition of the soldier art and photography submitted to this contest. The “Infantry Journal, Inc.” printed a small paperback booklet containing 215 photographs of pictures exhibited in the National Gallery of Art.

In August of 1944, the Museum of Modern Art, Armed Forces Program, organized an art center for veterans. Abby Rockefeller, in particular, had a strong interest in this project. Soldiers were invited to sketch, paint, or model under the guidance of skilled artists and craftsmen. Victor d’Amico, who was in charge of the Museum’s Education Department, was quoted in Russell Lynes book, Good Old Modern: An Intimate Portrait of the Museum of Modern Art. “I asked one fellow why he had taken up art and he said, Well, I just came back from destroying everything. I made up my mind that if I ever got out of the Army and out of the war I was never going to destroy another thing in my life, and I decided that art was the thing that I would do.” Another man said to d’Amico, “Art is like a good night’s sleep. You come away refreshed and at peace.”

In late October, 1944, an Arts and Crafts Branch of Special Services Division, Headquarters, European Theater of Operations was established. A versatile program of handcrafts flourished among the Army occupation troops.

The increased interest in crafts, rather than fine arts, at this time lead to a new name for the program: The “Handicrafts Branch.”

In 1945, the War Department published a new manual, “Soldier Handicrafts”, to help implement this new emphasis. The manual contained instructions for setting up crafts facilities, selecting as well as improvising tools and equipment, and basic information on a variety of arts and crafts.

As the Army moved from a combat to a peacetime role, the majority of crafts shops in the United States were equipped with woodworking power machinery for construction of furnishings and objects for personal living. Based on this new trend, in 1946 the program was again renamed, this time as “Manual Arts.”

At the same time, overseas programs were now employing local artists and craftsmen to operate the crafts facilities and instruct in a variety of arts and crafts. These highly skilled, indigenous instructors helped to stimulate the soldiers’ interest in the respective native cultures and artifacts. Thousands of troops overseas were encouraged to record their experiences on film. These photographs provided an invaluable means of communication between troops and their families back home.

When the war ended, the Navy had a firm of architects and draftsmen on contract to design ships. Since there was no longer a need for more ships, they were given a new assignment: To develop a series of instructional guides for arts and crafts. These were called “Hobby Manuals.” The Army was impressed with the quality of the Navy manuals and had them reprinted and adopted for use by Army troops. By 1948, the arts and crafts practiced throughout the Army were so varied and diverse that the program was renamed “Hobby Shops.” The first “Interservice Photography Contest” was held in 1948. Each service is eligible to send two years of their winning entries forward for the bi-annual interservice contest. In 1949, the first All Army Crafts Contest was also held. Once again, it was clear that the program title, “Hobby Shops” was misleading and overlapped into other forms of recreation.

In January, 1951, the program was designated as “The Army Crafts Program.” The program was recognized as an essential Army recreation activity along with sports, libraries, service clubs, soldier shows and soldier music. In the official statement of mission, professional leadership was emphasized to insure a balanced, progressive schedule of arts and crafts would be conducted in well-equipped, attractive facilities on all Army installations.

The program was now defined in terms of a “Basic Seven Program” which included: drawing and painting; ceramics and sculpture; metal work; leathercrafts; model building; photography and woodworking. These programs were to be conducted regularly in facilities known as the “multiple-type crafts shop.” For functional reasons, these facilities were divided into three separate technical areas for woodworking, photography and the arts and crafts.

During the Korean Conflict, the Army Crafts program utilized the personnel and shops in Japan to train soldiers to instruct crafts in Korea.

The mid-1950s saw more soldiers with cars and the need to repair their vehicles was recognized at Fort Carson, Colorado, by the craft director. Soldiers familiar with crafts shops knew that they had tools and so automotive crafts were established. By 1958, the Engineers published an Official Design Guide on Crafts Shops and Auto Crafts Shops. In 1959, the first All Army Art Contest was held. Once more, the Army Crafts Program responded to the needs of soldiers.

In the 1960’s, the war in Vietnam was a new challenge for the Army Crafts Program. The program had three levels of support; fixed facilities, mobile trailers designed as portable photo labs, and once again a “Kit Program.” The kit program originated at Headquarters, Department of Army, and it proved to be very popular with soldiers.

Tom Turner, today a well-known studio potter, was a soldier at Ft. Jackson, South Carolina in the 1960s. In the December 1990 / January 1991 “American Crafts” magazine, Turner, who had been a graduate student in art school when he was drafted, said the program was “a godsend.”

The Army Artist Program was re-initiated in cooperation with the Office of Military History to document the war in Vietnam. Soldier-artists were identified and teams were formed to draw and paint the events of this combat. Exhibitions of these soldier-artist works were produced and toured throughout the USA.

In 1970, the original name of the program, “Arts and Crafts”, was restored. In 1971, the “Arts and Crafts/Skills Development Program” was established for budget presentations and construction projects.

After the Vietnam demobilization, a new emphasis was placed on service to families and children of soldiers. To meet this new challenge in an environment of funding constraints the arts and crafts program began charging fees for classes. More part-time personnel were used to teach formal classes. Additionally, a need for more technical-vocational skills training for military personnel was met by close coordination with Army Education Programs. Army arts and crafts directors worked with soldiers during “Project Transition” to develop soldier skills for new careers in the public sector.

The main challenge in the 1980s and 90s was, and is, to become “self-sustaining.” Directors have been forced to find more ways to generate increased revenue to help defray the loss of appropriated funds and to cover the non-appropriated funds expenses of the program. Programs have added and increased emphasis on services such as, picture framing, gallery sales, engraving and trophy sales, etc... New programs such as multi-media computer graphics appeal to customers of the 1990’s.

The Gulf War presented the Army with some familiar challenges such as personnel off duty time in staging areas. Department of Army volunteer civilian recreation specialists were sent to Saudi Arabia in January, 1991, to organize recreation programs. Arts and crafts supplies were sent to the theater. An Army Humor Cartoon Contest was conducted for the soldiers in the Gulf, and arts and crafts programs were set up to meet soldier interests.

The increased operations tempo of the ‘90’s Army has once again placed emphasis on meeting the “recreation needs of deployed soldiers.” Arts and crafts activities and a variety of programs are assets commanders must have to meet the deployment challenges of these very different scenarios.

The Army arts and crafts program, no matter what it has been titled, has made some unique contributions for the military and our society in general. Army arts and crafts does not fit the narrow definition of drawing and painting or making ceramics, but the much larger sense of arts and crafts. It is painting and drawing. It also encompasses:

* all forms of design. (fabric, clothes, household appliances, dishes, vases, houses, automobiles, landscapes, computers, copy machines, desks, industrial machines, weapon systems, air crafts, roads, etc...)

* applied technology (photography, graphics, woodworking, sculpture, metal smithing, weaving and textiles, sewing, advertising, enameling, stained glass, pottery, charts, graphs, visual aides and even formats for correspondence...)

* a way of making learning fun, practical and meaningful (through the process of designing and making an object the creator must decide which materials and techniques to use, thereby engaging in creative problem solving and discovery) skills taught have military applications.

* a way to acquire quality items and save money by doing-it-yourself (making furniture, gifts, repairing things ...).

* a way to pursue college credit, through on post classes.

* a universal and non-verbal language (a picture is worth a thousand words).

* food for the human psyche, an element of morale that allows for individual expression (freedom).

* the celebration of human spirit and excellence (our highest form of public recognition is through a dedicated monument).

* physical and mental therapy (motor skill development, stress reduction, etc...).

* an activity that promotes self-reliance and self-esteem.

* the record of mankind, and in this case, of the Army.

What would the world be like today if this generally unknown program had not existed? To quantitatively state the overall impact of this program on the world is impossible. Millions of soldier citizens have been directly and indirectly exposed to arts and crafts because this program existed. One activity, photography can provide a clue to its impact. Soldiers encouraged to take pictures, beginning with WW II, have shared those images with family and friends. Classes in “How to Use a Camera” to “How to Develop Film and Print Pictures” were instrumental in soldiers seeing the results of using quality equipment. A good camera and lens could make a big difference in the quality of the print. They bought the top of the line equipment. When they were discharged from the Army or home on leave this new equipment was showed to the family and friends. Without this encouragement and exposure to photography many would not have recorded their personal experiences or known the difference quality equipment could make. Families and friends would not have had the opportunity to “see” the environment their soldier was living in without these photos. Germany, Italy, Korea, Japan, Panama, etc... were far away places that most had not visited.

As the twenty first century approaches, the predictions for an arts renaissance by Megatrends 2000 seem realistic based on the Army Arts and Crafts Program practical experience. In the April ‘95 issue of “American Demographics” magazine, an article titled “Generation X” fully supports that this is indeed the case today. Television and computers have greatly contributed to “Generation X” being more interested in the visual arts and crafts.

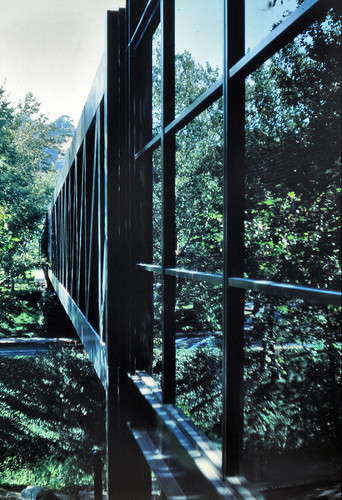

Army Photography Contest - 2004 - FMWRC - Arts and Crafts - Dream Scape

Image by familymwr

Photo by Master Sgt. Munnaf Joarder

To learn more about the annual U.S. Army Photography Competition, visit us online at www.armymwr.com

U.S. Army Arts and Crafts History

After World War I the reductions to the Army left the United States with a small force. The War Department faced monumental challenges in preparing for World War II. One of those challenges was soldier morale. Recreational activities for off duty time would be important. The arts and crafts program informally evolved to augment the needs of the War Department.

On January 9, 1941, the Secretary of War, Henry L. Stimson, appointed Frederick H. Osborn, a prominent U.S. businessman and philanthropist, Chairman of the War Department Committee on Education, Recreation and Community Service.

In 1940 and 1941, the United States involvement in World War II was more of sympathy and anticipation than of action. However, many different types of institutions were looking for ways to help the war effort. The Museum of Modern Art in New York was one of these institutions. In April, 1941, the Museum announced a poster competition, “Posters for National Defense.” The directors stated “The Museum feels that in a time of national emergency the artists of a country are as important an asset as men skilled in other fields, and that the nation’s first-rate talent should be utilized by the government for its official design work... Discussions have been held with officials of the Army and the Treasury who have expressed remarkable enthusiasm...”

In May 1941, the Museum exhibited “Britain at War”, a show selected by Sir Kenneth Clark, director of the National Gallery in London. The “Prize-Winning Defense Posters” were exhibited in July through September concurrently with “Britain at War.” The enormous overnight growth of the military force meant mobilization type construction at every camp. Construction was fast; facilities were not fancy; rather drab and depressing.

In 1941, the Fort Custer Army Illustrators, while on strenuous war games maneuvers in Tennessee, documented the exercise The Bulletin of the Museum of Modern Art, Vol. 9, No. 3 (Feb. 1942), described their work. “Results were astonishingly good; they showed serious devotion ...to the purpose of depicting the Army scene with unvarnished realism and a remarkable ability to capture this scene from the soldier’s viewpoint. Civilian amateur and professional artists had been transformed into soldier-artists. Reality and straightforward documentation had supplanted (replaced) the old romantic glorification and false dramatization of war and the slick suavity (charm) of commercial drawing.”

“In August of last year, Fort Custer Army Illustrators held an exhibition, the first of its kind in the new Army, at the Camp Service Club. Soldiers who saw the exhibition, many of whom had never been inside an art gallery, enjoyed it thoroughly. Civilian visitors, too, came and admired. The work of the group showed them a new aspect of the Army; there were many phases of Army life they had never seen or heard of before. Newspapers made much of it and, most important, the Army approved. Army officials saw that it was not only authentic material, but that here was a source of enlivenment (vitalization) to the Army and a vivid medium for conveying the Army’s purposes and processes to civilians and soldiers.”

Brigadier General Frederick H. Osborn and War Department leaders were concerned because few soldiers were using the off duty recreation areas that were available. Army commanders recognized that efficiency is directly correlated with morale, and that morale is largely determined from the manner in which an individual spends his own free time. Army morale enhancement through positive off duty recreation programs is critical in combat staging areas.

To encourage soldier use of programs, the facilities drab and uninviting environment had to be improved. A program utilizing talented artists and craftsmen to decorate day rooms, mess halls, recreation halls and other places of general assembly was established by the Facilities Section of Special Services. The purpose was to provide an environment that would reflect the military tradition, accomplishments and the high standard of army life. The fact that this work was to be done by the men themselves had the added benefit of contributing to the esprit de corps (teamwork, or group spirit) of the unit.

The plan was first tested in October of 1941, at Camp Davis, North Carolina. A studio workshop was set up and a group of soldier artists were placed on special duty to design and decorate the facilities. Additionally, evening recreation art classes were scheduled three times a week. A second test was established at Fort Belvoir, Virginia a month later. The success of these programs lead to more installations requesting the program.

After Pearl Harbor was bombed, the Museum of Modern Art appointed Mr. James Soby, to the position of Director of the Armed Service Program on January 15, 1942. The subsequent program became a combination of occupational therapy, exhibitions and morale-sustaining activities.

Through the efforts of Mr. Soby, the museum program included; a display of Fort Custer Army Illustrators work from February through April 5, 1942. The museum also included the work of soldier-photographers in this exhibit. On May 6, 1942, Mr. Soby opened an art sale of works donated by museum members. The sale was to raise funds for the Soldier Art Program of Special Services Division. The bulk of these proceeds were to be used to provide facilities and materials for soldier artists in Army camps throughout the country.

Members of the Museum had responded with paintings, sculptures, watercolors, gouaches, drawings, etchings and lithographs. Hundreds of works were received, including oils by Winslow Homer, Orozco, John Kane, Speicher, Eilshemius, de Chirico; watercolors by Burchfield and Dufy; drawings by Augustus John, Forain and Berman, and prints by Cezanne, Lautrec, Matisse and Bellows. The War Department plan using soldier-artists to decorate and improve buildings and grounds worked. Many artists who had been drafted into the Army volunteered to paint murals in waiting rooms and clubs, to decorate dayrooms, and to landscape grounds. For each artist at work there were a thousand troops who watched. These bystanders clamored to participate, and classes in drawing, painting, sculpture and photography were offered. Larger working space and more instructors were required to meet the growing demand. Civilian art instructors and local communities helped to meet this cultural need, by providing volunteer instruction and facilities.

Some proceeds from the Modern Museum of Art sale were used to print 25,000 booklets called “Interior Design and Soldier Art.” The booklet showed examples of soldier-artist murals that decorated places of general assembly. It was a guide to organizing, planning and executing the soldier-artist program. The balance of the art sale proceeds were used to purchase the initial arts and crafts furnishings for 350 Army installations in the USA.

In November, 1942, General Somervell directed that a group of artists be selected and dispatched to active theaters to paint war scenes with the stipulation that soldier artists would not paint in lieu of military duties.

Aileen Osborn Webb, sister of Brigadier General Frederick H. Osborn, launched the American Crafts Council in 1943. She was an early champion of the Army program.

While soldiers were participating in fixed facilities in the USA, many troops were being shipped overseas to Europe and the Pacific (1942-1945). They had long periods of idleness and waiting in staging areas. At that time the wounded were lying in hospitals, both on land and in ships at sea. The War Department and Red Cross responded by purchasing kits of arts and crafts tools and supplies to distribute to “these restless personnel.” A variety of small “Handicraft Kits” were distributed free of charge. Leathercraft, celluloid etching, knotting and braiding, metal tooling, drawing and clay modeling are examples of the types of kits sent.

In January, 1944, the Interior Design Soldier Artist program was more appropriately named the “Arts and Crafts Section” of Special Services. The mission was “to fulfill the natural human desire to create, provide opportunities for self-expression, serve old skills and develop new ones, and assist the entire recreation program through construction work, publicity, and decoration.”

The National Army Art Contest was planned for the late fall of 1944. In June of 1945, the National Gallery of Art in Washington D.C., for the first time in its history opened its facilities for the exhibition of the soldier art and photography submitted to this contest. The “Infantry Journal, Inc.” printed a small paperback booklet containing 215 photographs of pictures exhibited in the National Gallery of Art.

In August of 1944, the Museum of Modern Art, Armed Forces Program, organized an art center for veterans. Abby Rockefeller, in particular, had a strong interest in this project. Soldiers were invited to sketch, paint, or model under the guidance of skilled artists and craftsmen. Victor d’Amico, who was in charge of the Museum’s Education Department, was quoted in Russell Lynes book, Good Old Modern: An Intimate Portrait of the Museum of Modern Art. “I asked one fellow why he had taken up art and he said, Well, I just came back from destroying everything. I made up my mind that if I ever got out of the Army and out of the war I was never going to destroy another thing in my life, and I decided that art was the thing that I would do.” Another man said to d’Amico, “Art is like a good night’s sleep. You come away refreshed and at peace.”

In late October, 1944, an Arts and Crafts Branch of Special Services Division, Headquarters, European Theater of Operations was established. A versatile program of handcrafts flourished among the Army occupation troops.

The increased interest in crafts, rather than fine arts, at this time lead to a new name for the program: The “Handicrafts Branch.”

In 1945, the War Department published a new manual, “Soldier Handicrafts”, to help implement this new emphasis. The manual contained instructions for setting up crafts facilities, selecting as well as improvising tools and equipment, and basic information on a variety of arts and crafts.

As the Army moved from a combat to a peacetime role, the majority of crafts shops in the United States were equipped with woodworking power machinery for construction of furnishings and objects for personal living. Based on this new trend, in 1946 the program was again renamed, this time as “Manual Arts.”

At the same time, overseas programs were now employing local artists and craftsmen to operate the crafts facilities and instruct in a variety of arts and crafts. These highly skilled, indigenous instructors helped to stimulate the soldiers’ interest in the respective native cultures and artifacts. Thousands of troops overseas were encouraged to record their experiences on film. These photographs provided an invaluable means of communication between troops and their families back home.

When the war ended, the Navy had a firm of architects and draftsmen on contract to design ships. Since there was no longer a need for more ships, they were given a new assignment: To develop a series of instructional guides for arts and crafts. These were called “Hobby Manuals.” The Army was impressed with the quality of the Navy manuals and had them reprinted and adopted for use by Army troops. By 1948, the arts and crafts practiced throughout the Army were so varied and diverse that the program was renamed “Hobby Shops.” The first “Interservice Photography Contest” was held in 1948. Each service is eligible to send two years of their winning entries forward for the bi-annual interservice contest. In 1949, the first All Army Crafts Contest was also held. Once again, it was clear that the program title, “Hobby Shops” was misleading and overlapped into other forms of recreation.

In January, 1951, the program was designated as “The Army Crafts Program.” The program was recognized as an essential Army recreation activity along with sports, libraries, service clubs, soldier shows and soldier music. In the official statement of mission, professional leadership was emphasized to insure a balanced, progressive schedule of arts and crafts would be conducted in well-equipped, attractive facilities on all Army installations.

The program was now defined in terms of a “Basic Seven Program” which included: drawing and painting; ceramics and sculpture; metal work; leathercrafts; model building; photography and woodworking. These programs were to be conducted regularly in facilities known as the “multiple-type crafts shop.” For functional reasons, these facilities were divided into three separate technical areas for woodworking, photography and the arts and crafts.

During the Korean Conflict, the Army Crafts program utilized the personnel and shops in Japan to train soldiers to instruct crafts in Korea.

The mid-1950s saw more soldiers with cars and the need to repair their vehicles was recognized at Fort Carson, Colorado, by the craft director. Soldiers familiar with crafts shops knew that they had tools and so automotive crafts were established. By 1958, the Engineers published an Official Design Guide on Crafts Shops and Auto Crafts Shops. In 1959, the first All Army Art Contest was held. Once more, the Army Crafts Program responded to the needs of soldiers.

In the 1960’s, the war in Vietnam was a new challenge for the Army Crafts Program. The program had three levels of support; fixed facilities, mobile trailers designed as portable photo labs, and once again a “Kit Program.” The kit program originated at Headquarters, Department of Army, and it proved to be very popular with soldiers.

Tom Turner, today a well-known studio potter, was a soldier at Ft. Jackson, South Carolina in the 1960s. In the December 1990 / January 1991 “American Crafts” magazine, Turner, who had been a graduate student in art school when he was drafted, said the program was “a godsend.”

The Army Artist Program was re-initiated in cooperation with the Office of Military History to document the war in Vietnam. Soldier-artists were identified and teams were formed to draw and paint the events of this combat. Exhibitions of these soldier-artist works were produced and toured throughout the USA.

In 1970, the original name of the program, “Arts and Crafts”, was restored. In 1971, the “Arts and Crafts/Skills Development Program” was established for budget presentations and construction projects.

After the Vietnam demobilization, a new emphasis was placed on service to families and children of soldiers. To meet this new challenge in an environment of funding constraints the arts and crafts program began charging fees for classes. More part-time personnel were used to teach formal classes. Additionally, a need for more technical-vocational skills training for military personnel was met by close coordination with Army Education Programs. Army arts and crafts directors worked with soldiers during “Project Transition” to develop soldier skills for new careers in the public sector.

The main challenge in the 1980s and 90s was, and is, to become “self-sustaining.” Directors have been forced to find more ways to generate increased revenue to help defray the loss of appropriated funds and to cover the non-appropriated funds expenses of the program. Programs have added and increased emphasis on services such as, picture framing, gallery sales, engraving and trophy sales, etc... New programs such as multi-media computer graphics appeal to customers of the 1990’s.

The Gulf War presented the Army with some familiar challenges such as personnel off duty time in staging areas. Department of Army volunteer civilian recreation specialists were sent to Saudi Arabia in January, 1991, to organize recreation programs. Arts and crafts supplies were sent to the theater. An Army Humor Cartoon Contest was conducted for the soldiers in the Gulf, and arts and crafts programs were set up to meet soldier interests.

The increased operations tempo of the ‘90’s Army has once again placed emphasis on meeting the “recreation needs of deployed soldiers.” Arts and crafts activities and a variety of programs are assets commanders must have to meet the deployment challenges of these very different scenarios.

The Army arts and crafts program, no matter what it has been titled, has made some unique contributions for the military and our society in general. Army arts and crafts does not fit the narrow definition of drawing and painting or making ceramics, but the much larger sense of arts and crafts. It is painting and drawing. It also encompasses:

* all forms of design. (fabric, clothes, household appliances, dishes, vases, houses, automobiles, landscapes, computers, copy machines, desks, industrial machines, weapon systems, air crafts, roads, etc...)

* applied technology (photography, graphics, woodworking, sculpture, metal smithing, weaving and textiles, sewing, advertising, enameling, stained glass, pottery, charts, graphs, visual aides and even formats for correspondence...)

* a way of making learning fun, practical and meaningful (through the process of designing and making an object the creator must decide which materials and techniques to use, thereby engaging in creative problem solving and discovery) skills taught have military applications.

* a way to acquire quality items and save money by doing-it-yourself (making furniture, gifts, repairing things ...).

* a way to pursue college credit, through on post classes.

* a universal and non-verbal language (a picture is worth a thousand words).

* food for the human psyche, an element of morale that allows for individual expression (freedom).

* the celebration of human spirit and excellence (our highest form of public recognition is through a dedicated monument).

* physical and mental therapy (motor skill development, stress reduction, etc...).

* an activity that promotes self-reliance and self-esteem.

* the record of mankind, and in this case, of the Army.

What would the world be like today if this generally unknown program had not existed? To quantitatively state the overall impact of this program on the world is impossible. Millions of soldier citizens have been directly and indirectly exposed to arts and crafts because this program existed. One activity, photography can provide a clue to its impact. Soldiers encouraged to take pictures, beginning with WW II, have shared those images with family and friends. Classes in “How to Use a Camera” to “How to Develop Film and Print Pictures” were instrumental in soldiers seeing the results of using quality equipment. A good camera and lens could make a big difference in the quality of the print. They bought the top of the line equipment. When they were discharged from the Army or home on leave this new equipment was showed to the family and friends. Without this encouragement and exposure to photography many would not have recorded their personal experiences or known the difference quality equipment could make. Families and friends would not have had the opportunity to “see” the environment their soldier was living in without these photos. Germany, Italy, Korea, Japan, Panama, etc... were far away places that most had not visited.

As the twenty first century approaches, the predictions for an arts renaissance by Megatrends 2000 seem realistic based on the Army Arts and Crafts Program practical experience. In the April ‘95 issue of “American Demographics” magazine, an article titled “Generation X” fully supports that this is indeed the case today. Television and computers have greatly contributed to “Generation X” being more interested in the visual arts and crafts.

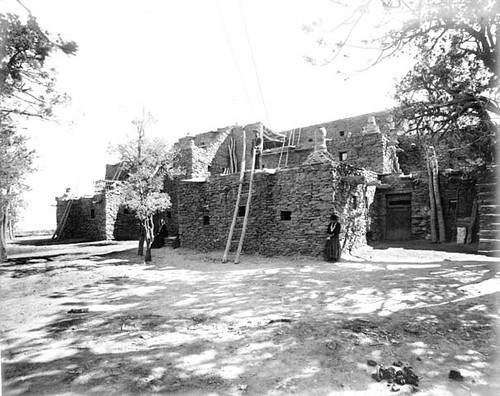

Army Photography Contest - 2004 - FMWRC - Arts and Crafts - Shadow Friends

Image by familymwr

Photo by Brittney Rankin

To learn more about the annual U.S. Army Photography Competition, visit us online at www.armymwr.com

U.S. Army Arts and Crafts History

After World War I the reductions to the Army left the United States with a small force. The War Department faced monumental challenges in preparing for World War II. One of those challenges was soldier morale. Recreational activities for off duty time would be important. The arts and crafts program informally evolved to augment the needs of the War Department.

On January 9, 1941, the Secretary of War, Henry L. Stimson, appointed Frederick H. Osborn, a prominent U.S. businessman and philanthropist, Chairman of the War Department Committee on Education, Recreation and Community Service.

In 1940 and 1941, the United States involvement in World War II was more of sympathy and anticipation than of action. However, many different types of institutions were looking for ways to help the war effort. The Museum of Modern Art in New York was one of these institutions. In April, 1941, the Museum announced a poster competition, “Posters for National Defense.” The directors stated “The Museum feels that in a time of national emergency the artists of a country are as important an asset as men skilled in other fields, and that the nation’s first-rate talent should be utilized by the government for its official design work... Discussions have been held with officials of the Army and the Treasury who have expressed remarkable enthusiasm...”

In May 1941, the Museum exhibited “Britain at War”, a show selected by Sir Kenneth Clark, director of the National Gallery in London. The “Prize-Winning Defense Posters” were exhibited in July through September concurrently with “Britain at War.” The enormous overnight growth of the military force meant mobilization type construction at every camp. Construction was fast; facilities were not fancy; rather drab and depressing.

In 1941, the Fort Custer Army Illustrators, while on strenuous war games maneuvers in Tennessee, documented the exercise The Bulletin of the Museum of Modern Art, Vol. 9, No. 3 (Feb. 1942), described their work. “Results were astonishingly good; they showed serious devotion ...to the purpose of depicting the Army scene with unvarnished realism and a remarkable ability to capture this scene from the soldier’s viewpoint. Civilian amateur and professional artists had been transformed into soldier-artists. Reality and straightforward documentation had supplanted (replaced) the old romantic glorification and false dramatization of war and the slick suavity (charm) of commercial drawing.”

“In August of last year, Fort Custer Army Illustrators held an exhibition, the first of its kind in the new Army, at the Camp Service Club. Soldiers who saw the exhibition, many of whom had never been inside an art gallery, enjoyed it thoroughly. Civilian visitors, too, came and admired. The work of the group showed them a new aspect of the Army; there were many phases of Army life they had never seen or heard of before. Newspapers made much of it and, most important, the Army approved. Army officials saw that it was not only authentic material, but that here was a source of enlivenment (vitalization) to the Army and a vivid medium for conveying the Army’s purposes and processes to civilians and soldiers.”

Brigadier General Frederick H. Osborn and War Department leaders were concerned because few soldiers were using the off duty recreation areas that were available. Army commanders recognized that efficiency is directly correlated with morale, and that morale is largely determined from the manner in which an individual spends his own free time. Army morale enhancement through positive off duty recreation programs is critical in combat staging areas.

To encourage soldier use of programs, the facilities drab and uninviting environment had to be improved. A program utilizing talented artists and craftsmen to decorate day rooms, mess halls, recreation halls and other places of general assembly was established by the Facilities Section of Special Services. The purpose was to provide an environment that would reflect the military tradition, accomplishments and the high standard of army life. The fact that this work was to be done by the men themselves had the added benefit of contributing to the esprit de corps (teamwork, or group spirit) of the unit.

The plan was first tested in October of 1941, at Camp Davis, North Carolina. A studio workshop was set up and a group of soldier artists were placed on special duty to design and decorate the facilities. Additionally, evening recreation art classes were scheduled three times a week. A second test was established at Fort Belvoir, Virginia a month later. The success of these programs lead to more installations requesting the program.

After Pearl Harbor was bombed, the Museum of Modern Art appointed Mr. James Soby, to the position of Director of the Armed Service Program on January 15, 1942. The subsequent program became a combination of occupational therapy, exhibitions and morale-sustaining activities.

Through the efforts of Mr. Soby, the museum program included; a display of Fort Custer Army Illustrators work from February through April 5, 1942. The museum also included the work of soldier-photographers in this exhibit. On May 6, 1942, Mr. Soby opened an art sale of works donated by museum members. The sale was to raise funds for the Soldier Art Program of Special Services Division. The bulk of these proceeds were to be used to provide facilities and materials for soldier artists in Army camps throughout the country.

Members of the Museum had responded with paintings, sculptures, watercolors, gouaches, drawings, etchings and lithographs. Hundreds of works were received, including oils by Winslow Homer, Orozco, John Kane, Speicher, Eilshemius, de Chirico; watercolors by Burchfield and Dufy; drawings by Augustus John, Forain and Berman, and prints by Cezanne, Lautrec, Matisse and Bellows. The War Department plan using soldier-artists to decorate and improve buildings and grounds worked. Many artists who had been drafted into the Army volunteered to paint murals in waiting rooms and clubs, to decorate dayrooms, and to landscape grounds. For each artist at work there were a thousand troops who watched. These bystanders clamored to participate, and classes in drawing, painting, sculpture and photography were offered. Larger working space and more instructors were required to meet the growing demand. Civilian art instructors and local communities helped to meet this cultural need, by providing volunteer instruction and facilities.

Some proceeds from the Modern Museum of Art sale were used to print 25,000 booklets called “Interior Design and Soldier Art.” The booklet showed examples of soldier-artist murals that decorated places of general assembly. It was a guide to organizing, planning and executing the soldier-artist program. The balance of the art sale proceeds were used to purchase the initial arts and crafts furnishings for 350 Army installations in the USA.

In November, 1942, General Somervell directed that a group of artists be selected and dispatched to active theaters to paint war scenes with the stipulation that soldier artists would not paint in lieu of military duties.

Aileen Osborn Webb, sister of Brigadier General Frederick H. Osborn, launched the American Crafts Council in 1943. She was an early champion of the Army program.

While soldiers were participating in fixed facilities in the USA, many troops were being shipped overseas to Europe and the Pacific (1942-1945). They had long periods of idleness and waiting in staging areas. At that time the wounded were lying in hospitals, both on land and in ships at sea. The War Department and Red Cross responded by purchasing kits of arts and crafts tools and supplies to distribute to “these restless personnel.” A variety of small “Handicraft Kits” were distributed free of charge. Leathercraft, celluloid etching, knotting and braiding, metal tooling, drawing and clay modeling are examples of the types of kits sent.

In January, 1944, the Interior Design Soldier Artist program was more appropriately named the “Arts and Crafts Section” of Special Services. The mission was “to fulfill the natural human desire to create, provide opportunities for self-expression, serve old skills and develop new ones, and assist the entire recreation program through construction work, publicity, and decoration.”

The National Army Art Contest was planned for the late fall of 1944. In June of 1945, the National Gallery of Art in Washington D.C., for the first time in its history opened its facilities for the exhibition of the soldier art and photography submitted to this contest. The “Infantry Journal, Inc.” printed a small paperback booklet containing 215 photographs of pictures exhibited in the National Gallery of Art.

In August of 1944, the Museum of Modern Art, Armed Forces Program, organized an art center for veterans. Abby Rockefeller, in particular, had a strong interest in this project. Soldiers were invited to sketch, paint, or model under the guidance of skilled artists and craftsmen. Victor d’Amico, who was in charge of the Museum’s Education Department, was quoted in Russell Lynes book, Good Old Modern: An Intimate Portrait of the Museum of Modern Art. “I asked one fellow why he had taken up art and he said, Well, I just came back from destroying everything. I made up my mind that if I ever got out of the Army and out of the war I was never going to destroy another thing in my life, and I decided that art was the thing that I would do.” Another man said to d’Amico, “Art is like a good night’s sleep. You come away refreshed and at peace.”

In late October, 1944, an Arts and Crafts Branch of Special Services Division, Headquarters, European Theater of Operations was established. A versatile program of handcrafts flourished among the Army occupation troops.

The increased interest in crafts, rather than fine arts, at this time lead to a new name for the program: The “Handicrafts Branch.”

In 1945, the War Department published a new manual, “Soldier Handicrafts”, to help implement this new emphasis. The manual contained instructions for setting up crafts facilities, selecting as well as improvising tools and equipment, and basic information on a variety of arts and crafts.

As the Army moved from a combat to a peacetime role, the majority of crafts shops in the United States were equipped with woodworking power machinery for construction of furnishings and objects for personal living. Based on this new trend, in 1946 the program was again renamed, this time as “Manual Arts.”

At the same time, overseas programs were now employing local artists and craftsmen to operate the crafts facilities and instruct in a variety of arts and crafts. These highly skilled, indigenous instructors helped to stimulate the soldiers’ interest in the respective native cultures and artifacts. Thousands of troops overseas were encouraged to record their experiences on film. These photographs provided an invaluable means of communication between troops and their families back home.

When the war ended, the Navy had a firm of architects and draftsmen on contract to design ships. Since there was no longer a need for more ships, they were given a new assignment: To develop a series of instructional guides for arts and crafts. These were called “Hobby Manuals.” The Army was impressed with the quality of the Navy manuals and had them reprinted and adopted for use by Army troops. By 1948, the arts and crafts practiced throughout the Army were so varied and diverse that the program was renamed “Hobby Shops.” The first “Interservice Photography Contest” was held in 1948. Each service is eligible to send two years of their winning entries forward for the bi-annual interservice contest. In 1949, the first All Army Crafts Contest was also held. Once again, it was clear that the program title, “Hobby Shops” was misleading and overlapped into other forms of recreation.

In January, 1951, the program was designated as “The Army Crafts Program.” The program was recognized as an essential Army recreation activity along with sports, libraries, service clubs, soldier shows and soldier music. In the official statement of mission, professional leadership was emphasized to insure a balanced, progressive schedule of arts and crafts would be conducted in well-equipped, attractive facilities on all Army installations.

The program was now defined in terms of a “Basic Seven Program” which included: drawing and painting; ceramics and sculpture; metal work; leathercrafts; model building; photography and woodworking. These programs were to be conducted regularly in facilities known as the “multiple-type crafts shop.” For functional reasons, these facilities were divided into three separate technical areas for woodworking, photography and the arts and crafts.

During the Korean Conflict, the Army Crafts program utilized the personnel and shops in Japan to train soldiers to instruct crafts in Korea.

The mid-1950s saw more soldiers with cars and the need to repair their vehicles was recognized at Fort Carson, Colorado, by the craft director. Soldiers familiar with crafts shops knew that they had tools and so automotive crafts were established. By 1958, the Engineers published an Official Design Guide on Crafts Shops and Auto Crafts Shops. In 1959, the first All Army Art Contest was held. Once more, the Army Crafts Program responded to the needs of soldiers.

In the 1960’s, the war in Vietnam was a new challenge for the Army Crafts Program. The program had three levels of support; fixed facilities, mobile trailers designed as portable photo labs, and once again a “Kit Program.” The kit program originated at Headquarters, Department of Army, and it proved to be very popular with soldiers.

Tom Turner, today a well-known studio potter, was a soldier at Ft. Jackson, South Carolina in the 1960s. In the December 1990 / January 1991 “American Crafts” magazine, Turner, who had been a graduate student in art school when he was drafted, said the program was “a godsend.”

The Army Artist Program was re-initiated in cooperation with the Office of Military History to document the war in Vietnam. Soldier-artists were identified and teams were formed to draw and paint the events of this combat. Exhibitions of these soldier-artist works were produced and toured throughout the USA.

In 1970, the original name of the program, “Arts and Crafts”, was restored. In 1971, the “Arts and Crafts/Skills Development Program” was established for budget presentations and construction projects.

After the Vietnam demobilization, a new emphasis was placed on service to families and children of soldiers. To meet this new challenge in an environment of funding constraints the arts and crafts program began charging fees for classes. More part-time personnel were used to teach formal classes. Additionally, a need for more technical-vocational skills training for military personnel was met by close coordination with Army Education Programs. Army arts and crafts directors worked with soldiers during “Project Transition” to develop soldier skills for new careers in the public sector.

The main challenge in the 1980s and 90s was, and is, to become “self-sustaining.” Directors have been forced to find more ways to generate increased revenue to help defray the loss of appropriated funds and to cover the non-appropriated funds expenses of the program. Programs have added and increased emphasis on services such as, picture framing, gallery sales, engraving and trophy sales, etc... New programs such as multi-media computer graphics appeal to customers of the 1990’s.

The Gulf War presented the Army with some familiar challenges such as personnel off duty time in staging areas. Department of Army volunteer civilian recreation specialists were sent to Saudi Arabia in January, 1991, to organize recreation programs. Arts and crafts supplies were sent to the theater. An Army Humor Cartoon Contest was conducted for the soldiers in the Gulf, and arts and crafts programs were set up to meet soldier interests.

The increased operations tempo of the ‘90’s Army has once again placed emphasis on meeting the “recreation needs of deployed soldiers.” Arts and crafts activities and a variety of programs are assets commanders must have to meet the deployment challenges of these very different scenarios.

The Army arts and crafts program, no matter what it has been titled, has made some unique contributions for the military and our society in general. Army arts and crafts does not fit the narrow definition of drawing and painting or making ceramics, but the much larger sense of arts and crafts. It is painting and drawing. It also encompasses:

* all forms of design. (fabric, clothes, household appliances, dishes, vases, houses, automobiles, landscapes, computers, copy machines, desks, industrial machines, weapon systems, air crafts, roads, etc...)

* applied technology (photography, graphics, woodworking, sculpture, metal smithing, weaving and textiles, sewing, advertising, enameling, stained glass, pottery, charts, graphs, visual aides and even formats for correspondence...)

* a way of making learning fun, practical and meaningful (through the process of designing and making an object the creator must decide which materials and techniques to use, thereby engaging in creative problem solving and discovery) skills taught have military applications.

* a way to acquire quality items and save money by doing-it-yourself (making furniture, gifts, repairing things ...).

* a way to pursue college credit, through on post classes.

* a universal and non-verbal language (a picture is worth a thousand words).

* food for the human psyche, an element of morale that allows for individual expression (freedom).

* the celebration of human spirit and excellence (our highest form of public recognition is through a dedicated monument).

* physical and mental therapy (motor skill development, stress reduction, etc...).

* an activity that promotes self-reliance and self-esteem.

* the record of mankind, and in this case, of the Army.

What would the world be like today if this generally unknown program had not existed? To quantitatively state the overall impact of this program on the world is impossible. Millions of soldier citizens have been directly and indirectly exposed to arts and crafts because this program existed. One activity, photography can provide a clue to its impact. Soldiers encouraged to take pictures, beginning with WW II, have shared those images with family and friends. Classes in “How to Use a Camera” to “How to Develop Film and Print Pictures” were instrumental in soldiers seeing the results of using quality equipment. A good camera and lens could make a big difference in the quality of the print. They bought the top of the line equipment. When they were discharged from the Army or home on leave this new equipment was showed to the family and friends. Without this encouragement and exposure to photography many would not have recorded their personal experiences or known the difference quality equipment could make. Families and friends would not have had the opportunity to “see” the environment their soldier was living in without these photos. Germany, Italy, Korea, Japan, Panama, etc... were far away places that most had not visited.

As the twenty first century approaches, the predictions for an arts renaissance by Megatrends 2000 seem realistic based on the Army Arts and Crafts Program practical experience. In the April ‘95 issue of “American Demographics” magazine, an article titled “Generation X” fully supports that this is indeed the case today. Television and computers have greatly contributed to “Generation X” being more interested in the visual arts and crafts.

Army Photography Contest - 2004 - FMWRC - Arts and Crafts - Valor Never Dies

Image by familymwr

Photo by Robert LaPolice

To learn more about the annual U.S. Army Photography Competition, visit us online at www.armymwr.com

U.S. Army Arts and Crafts History

After World War I the reductions to the Army left the United States with a small force. The War Department faced monumental challenges in preparing for World War II. One of those challenges was soldier morale. Recreational activities for off duty time would be important. The arts and crafts program informally evolved to augment the needs of the War Department.

On January 9, 1941, the Secretary of War, Henry L. Stimson, appointed Frederick H. Osborn, a prominent U.S. businessman and philanthropist, Chairman of the War Department Committee on Education, Recreation and Community Service.

In 1940 and 1941, the United States involvement in World War II was more of sympathy and anticipation than of action. However, many different types of institutions were looking for ways to help the war effort. The Museum of Modern Art in New York was one of these institutions. In April, 1941, the Museum announced a poster competition, “Posters for National Defense.” The directors stated “The Museum feels that in a time of national emergency the artists of a country are as important an asset as men skilled in other fields, and that the nation’s first-rate talent should be utilized by the government for its official design work... Discussions have been held with officials of the Army and the Treasury who have expressed remarkable enthusiasm...”

In May 1941, the Museum exhibited “Britain at War”, a show selected by Sir Kenneth Clark, director of the National Gallery in London. The “Prize-Winning Defense Posters” were exhibited in July through September concurrently with “Britain at War.” The enormous overnight growth of the military force meant mobilization type construction at every camp. Construction was fast; facilities were not fancy; rather drab and depressing.

In 1941, the Fort Custer Army Illustrators, while on strenuous war games maneuvers in Tennessee, documented the exercise The Bulletin of the Museum of Modern Art, Vol. 9, No. 3 (Feb. 1942), described their work. “Results were astonishingly good; they showed serious devotion ...to the purpose of depicting the Army scene with unvarnished realism and a remarkable ability to capture this scene from the soldier’s viewpoint. Civilian amateur and professional artists had been transformed into soldier-artists. Reality and straightforward documentation had supplanted (replaced) the old romantic glorification and false dramatization of war and the slick suavity (charm) of commercial drawing.”

“In August of last year, Fort Custer Army Illustrators held an exhibition, the first of its kind in the new Army, at the Camp Service Club. Soldiers who saw the exhibition, many of whom had never been inside an art gallery, enjoyed it thoroughly. Civilian visitors, too, came and admired. The work of the group showed them a new aspect of the Army; there were many phases of Army life they had never seen or heard of before. Newspapers made much of it and, most important, the Army approved. Army officials saw that it was not only authentic material, but that here was a source of enlivenment (vitalization) to the Army and a vivid medium for conveying the Army’s purposes and processes to civilians and soldiers.”

Brigadier General Frederick H. Osborn and War Department leaders were concerned because few soldiers were using the off duty recreation areas that were available. Army commanders recognized that efficiency is directly correlated with morale, and that morale is largely determined from the manner in which an individual spends his own free time. Army morale enhancement through positive off duty recreation programs is critical in combat staging areas.

To encourage soldier use of programs, the facilities drab and uninviting environment had to be improved. A program utilizing talented artists and craftsmen to decorate day rooms, mess halls, recreation halls and other places of general assembly was established by the Facilities Section of Special Services. The purpose was to provide an environment that would reflect the military tradition, accomplishments and the high standard of army life. The fact that this work was to be done by the men themselves had the added benefit of contributing to the esprit de corps (teamwork, or group spirit) of the unit.

The plan was first tested in October of 1941, at Camp Davis, North Carolina. A studio workshop was set up and a group of soldier artists were placed on special duty to design and decorate the facilities. Additionally, evening recreation art classes were scheduled three times a week. A second test was established at Fort Belvoir, Virginia a month later. The success of these programs lead to more installations requesting the program.

After Pearl Harbor was bombed, the Museum of Modern Art appointed Mr. James Soby, to the position of Director of the Armed Service Program on January 15, 1942. The subsequent program became a combination of occupational therapy, exhibitions and morale-sustaining activities.

Through the efforts of Mr. Soby, the museum program included; a display of Fort Custer Army Illustrators work from February through April 5, 1942. The museum also included the work of soldier-photographers in this exhibit. On May 6, 1942, Mr. Soby opened an art sale of works donated by museum members. The sale was to raise funds for the Soldier Art Program of Special Services Division. The bulk of these proceeds were to be used to provide facilities and materials for soldier artists in Army camps throughout the country.

Members of the Museum had responded with paintings, sculptures, watercolors, gouaches, drawings, etchings and lithographs. Hundreds of works were received, including oils by Winslow Homer, Orozco, John Kane, Speicher, Eilshemius, de Chirico; watercolors by Burchfield and Dufy; drawings by Augustus John, Forain and Berman, and prints by Cezanne, Lautrec, Matisse and Bellows. The War Department plan using soldier-artists to decorate and improve buildings and grounds worked. Many artists who had been drafted into the Army volunteered to paint murals in waiting rooms and clubs, to decorate dayrooms, and to landscape grounds. For each artist at work there were a thousand troops who watched. These bystanders clamored to participate, and classes in drawing, painting, sculpture and photography were offered. Larger working space and more instructors were required to meet the growing demand. Civilian art instructors and local communities helped to meet this cultural need, by providing volunteer instruction and facilities.

Some proceeds from the Modern Museum of Art sale were used to print 25,000 booklets called “Interior Design and Soldier Art.” The booklet showed examples of soldier-artist murals that decorated places of general assembly. It was a guide to organizing, planning and executing the soldier-artist program. The balance of the art sale proceeds were used to purchase the initial arts and crafts furnishings for 350 Army installations in the USA.

In November, 1942, General Somervell directed that a group of artists be selected and dispatched to active theaters to paint war scenes with the stipulation that soldier artists would not paint in lieu of military duties.

Aileen Osborn Webb, sister of Brigadier General Frederick H. Osborn, launched the American Crafts Council in 1943. She was an early champion of the Army program.

While soldiers were participating in fixed facilities in the USA, many troops were being shipped overseas to Europe and the Pacific (1942-1945). They had long periods of idleness and waiting in staging areas. At that time the wounded were lying in hospitals, both on land and in ships at sea. The War Department and Red Cross responded by purchasing kits of arts and crafts tools and supplies to distribute to “these restless personnel.” A variety of small “Handicraft Kits” were distributed free of charge. Leathercraft, celluloid etching, knotting and braiding, metal tooling, drawing and clay modeling are examples of the types of kits sent.

In January, 1944, the Interior Design Soldier Artist program was more appropriately named the “Arts and Crafts Section” of Special Services. The mission was “to fulfill the natural human desire to create, provide opportunities for self-expression, serve old skills and develop new ones, and assist the entire recreation program through construction work, publicity, and decoration.”

The National Army Art Contest was planned for the late fall of 1944. In June of 1945, the National Gallery of Art in Washington D.C., for the first time in its history opened its facilities for the exhibition of the soldier art and photography submitted to this contest. The “Infantry Journal, Inc.” printed a small paperback booklet containing 215 photographs of pictures exhibited in the National Gallery of Art.

In August of 1944, the Museum of Modern Art, Armed Forces Program, organized an art center for veterans. Abby Rockefeller, in particular, had a strong interest in this project. Soldiers were invited to sketch, paint, or model under the guidance of skilled artists and craftsmen. Victor d’Amico, who was in charge of the Museum’s Education Department, was quoted in Russell Lynes book, Good Old Modern: An Intimate Portrait of the Museum of Modern Art. “I asked one fellow why he had taken up art and he said, Well, I just came back from destroying everything. I made up my mind that if I ever got out of the Army and out of the war I was never going to destroy another thing in my life, and I decided that art was the thing that I would do.” Another man said to d’Amico, “Art is like a good night’s sleep. You come away refreshed and at peace.”

In late October, 1944, an Arts and Crafts Branch of Special Services Division, Headquarters, European Theater of Operations was established. A versatile program of handcrafts flourished among the Army occupation troops.

The increased interest in crafts, rather than fine arts, at this time lead to a new name for the program: The “Handicrafts Branch.”

In 1945, the War Department published a new manual, “Soldier Handicrafts”, to help implement this new emphasis. The manual contained instructions for setting up crafts facilities, selecting as well as improvising tools and equipment, and basic information on a variety of arts and crafts.

As the Army moved from a combat to a peacetime role, the majority of crafts shops in the United States were equipped with woodworking power machinery for construction of furnishings and objects for personal living. Based on this new trend, in 1946 the program was again renamed, this time as “Manual Arts.”

At the same time, overseas programs were now employing local artists and craftsmen to operate the crafts facilities and instruct in a variety of arts and crafts. These highly skilled, indigenous instructors helped to stimulate the soldiers’ interest in the respective native cultures and artifacts. Thousands of troops overseas were encouraged to record their experiences on film. These photographs provided an invaluable means of communication between troops and their families back home.

When the war ended, the Navy had a firm of architects and draftsmen on contract to design ships. Since there was no longer a need for more ships, they were given a new assignment: To develop a series of instructional guides for arts and crafts. These were called “Hobby Manuals.” The Army was impressed with the quality of the Navy manuals and had them reprinted and adopted for use by Army troops. By 1948, the arts and crafts practiced throughout the Army were so varied and diverse that the program was renamed “Hobby Shops.” The first “Interservice Photography Contest” was held in 1948. Each service is eligible to send two years of their winning entries forward for the bi-annual interservice contest. In 1949, the first All Army Crafts Contest was also held. Once again, it was clear that the program title, “Hobby Shops” was misleading and overlapped into other forms of recreation.

In January, 1951, the program was designated as “The Army Crafts Program.” The program was recognized as an essential Army recreation activity along with sports, libraries, service clubs, soldier shows and soldier music. In the official statement of mission, professional leadership was emphasized to insure a balanced, progressive schedule of arts and crafts would be conducted in well-equipped, attractive facilities on all Army installations.

The program was now defined in terms of a “Basic Seven Program” which included: drawing and painting; ceramics and sculpture; metal work; leathercrafts; model building; photography and woodworking. These programs were to be conducted regularly in facilities known as the “multiple-type crafts shop.” For functional reasons, these facilities were divided into three separate technical areas for woodworking, photography and the arts and crafts.

During the Korean Conflict, the Army Crafts program utilized the personnel and shops in Japan to train soldiers to instruct crafts in Korea.

The mid-1950s saw more soldiers with cars and the need to repair their vehicles was recognized at Fort Carson, Colorado, by the craft director. Soldiers familiar with crafts shops knew that they had tools and so automotive crafts were established. By 1958, the Engineers published an Official Design Guide on Crafts Shops and Auto Crafts Shops. In 1959, the first All Army Art Contest was held. Once more, the Army Crafts Program responded to the needs of soldiers.

In the 1960’s, the war in Vietnam was a new challenge for the Army Crafts Program. The program had three levels of support; fixed facilities, mobile trailers designed as portable photo labs, and once again a “Kit Program.” The kit program originated at Headquarters, Department of Army, and it proved to be very popular with soldiers.

Tom Turner, today a well-known studio potter, was a soldier at Ft. Jackson, South Carolina in the 1960s. In the December 1990 / January 1991 “American Crafts” magazine, Turner, who had been a graduate student in art school when he was drafted, said the program was “a godsend.”

The Army Artist Program was re-initiated in cooperation with the Office of Military History to document the war in Vietnam. Soldier-artists were identified and teams were formed to draw and paint the events of this combat. Exhibitions of these soldier-artist works were produced and toured throughout the USA.

In 1970, the original name of the program, “Arts and Crafts”, was restored. In 1971, the “Arts and Crafts/Skills Development Program” was established for budget presentations and construction projects.

After the Vietnam demobilization, a new emphasis was placed on service to families and children of soldiers. To meet this new challenge in an environment of funding constraints the arts and crafts program began charging fees for classes. More part-time personnel were used to teach formal classes. Additionally, a need for more technical-vocational skills training for military personnel was met by close coordination with Army Education Programs. Army arts and crafts directors worked with soldiers during “Project Transition” to develop soldier skills for new careers in the public sector.

The main challenge in the 1980s and 90s was, and is, to become “self-sustaining.” Directors have been forced to find more ways to generate increased revenue to help defray the loss of appropriated funds and to cover the non-appropriated funds expenses of the program. Programs have added and increased emphasis on services such as, picture framing, gallery sales, engraving and trophy sales, etc... New programs such as multi-media computer graphics appeal to customers of the 1990’s.

The Gulf War presented the Army with some familiar challenges such as personnel off duty time in staging areas. Department of Army volunteer civilian recreation specialists were sent to Saudi Arabia in January, 1991, to organize recreation programs. Arts and crafts supplies were sent to the theater. An Army Humor Cartoon Contest was conducted for the soldiers in the Gulf, and arts and crafts programs were set up to meet soldier interests.

The increased operations tempo of the ‘90’s Army has once again placed emphasis on meeting the “recreation needs of deployed soldiers.” Arts and crafts activities and a variety of programs are assets commanders must have to meet the deployment challenges of these very different scenarios.

The Army arts and crafts program, no matter what it has been titled, has made some unique contributions for the military and our society in general. Army arts and crafts does not fit the narrow definition of drawing and painting or making ceramics, but the much larger sense of arts and crafts. It is painting and drawing. It also encompasses:

* all forms of design. (fabric, clothes, household appliances, dishes, vases, houses, automobiles, landscapes, computers, copy machines, desks, industrial machines, weapon systems, air crafts, roads, etc...)

* applied technology (photography, graphics, woodworking, sculpture, metal smithing, weaving and textiles, sewing, advertising, enameling, stained glass, pottery, charts, graphs, visual aides and even formats for correspondence...)

* a way of making learning fun, practical and meaningful (through the process of designing and making an object the creator must decide which materials and techniques to use, thereby engaging in creative problem solving and discovery) skills taught have military applications.

* a way to acquire quality items and save money by doing-it-yourself (making furniture, gifts, repairing things ...).

* a way to pursue college credit, through on post classes.

* a universal and non-verbal language (a picture is worth a thousand words).

* food for the human psyche, an element of morale that allows for individual expression (freedom).

* the celebration of human spirit and excellence (our highest form of public recognition is through a dedicated monument).

* physical and mental therapy (motor skill development, stress reduction, etc...).

* an activity that promotes self-reliance and self-esteem.

* the record of mankind, and in this case, of the Army.